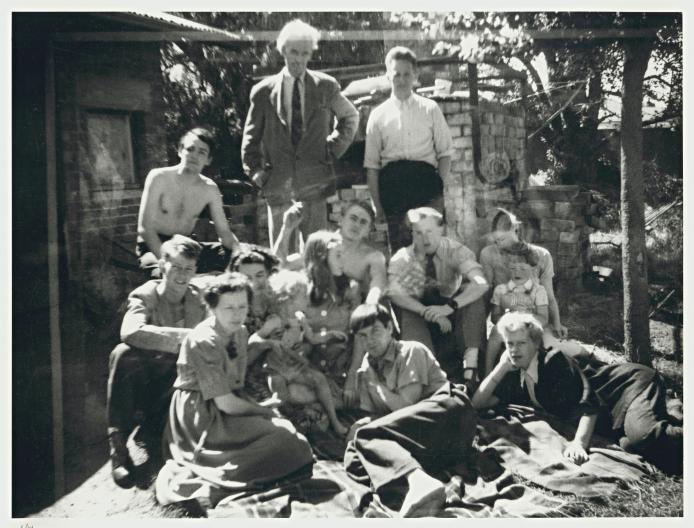

A dynasty is defined as a family spanning a number of generations—the most notable dynasties have the trappings of wealth, power and ambition. But the Boyd family, a complex network of artistic individuals often referred to as Australia’s pre-eminent dynasty of artists, does not bode well with the label of ‘dynasty’. A new exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (Australia), ‘Outer Circle: The Boyds and the Murrumbeena Artists’, explores the colourful history of the down-to-earth Boyd family of artists and friends between 1913 and the early 1960s. This was a time when artist and potter Merric Boyd (1888–1959) and his family occupied an overgrown semi-rural double block called Open Country in Murrumbeena, a suburb south east of Melbourne. The property abutted Murrumbeena Creek and the remnants of the short-lived Outer Circle railway line. This extraordinary place was also a magnet for artists and writers who were seeking to share ideas about art and life.

Family and friends at Open Country, c.1951, (Left to right, back) David Boyd, Merric Boyd, Hatton Beck, (Left to right centre) Guy Boyd, Lucy Boyd (with child), Mary Boyd, John Perceval, unidentified, Yvonne and son Jamie Boyd, (Left to right, front) Doris Boyd, Arthur Boyd, Joy Hester

It all began in 1913 when Merric Boyd began to build a small weatherboard house and pottery studio, including kiln, at Open Country. In 1915 Merric married Doris Gough and they had five children: Lucy, Arthur, Guy, David and Mary. Merric produced his distinctive wheel-thrown and hand-modelled earthenware forms. Doris, an enthusiastic amateur artist, often decorated pottery that Merric created. The organic works typically drew inspiration from Australian flora and fauna, characterised by sinuous, charming forms and glazed with a palette that reflected the earthy, muted colours of the Australian bush. Many of these sculptured animals, pots, lamps, jugs and vases can be seen in the first room of the exhibition.

“The first impulse of the maker of hand pottery is to obtain pleasure in making and decorating an article, and making that pleasure intelligible to others. Besides that, it is his ultimate aim to produce something beautiful which will give pleasure to all beholders. The use of our own flora and fauna is of the first importance.” (Merric Boyd)

The Boyd children had every opportunity to develop an artist’s imagination as they grew up in the wild Open Country garden with trees to climb and places to hide. They were given lumps of clay and pencils at an early age, and so they busied themselves making pots and sketching. But they stood out from the other children at the local Murrumbeena Primary School as being ‘wild’. A home life sustained by art and creativity was normal to the Boyds, but their suburban neighbours of the 1930s were conservative: practicality was the key to survival as most struggled to make ends meet. Merric and Doris were determined to make a living selling their pottery, but they too struggled financially. They commuted into Melbourne on the train on a regular basis, carrying their heavy wares, and walking from retailer to retailer, offering their hand-made pots, vases and decanter sets for sale. Merric had early success, but when his kiln caught fire overnight in 1926, the trauma affected his output and exacerbated his epileptic condition. Nevertheless, Merric continued to oversee the comings and goings of his beloved family as he remained living and working at Open Country, encouraging the integration of painting, pottery, sculpture, music and literature.

Emma Minnie Boyd, ‘Interior with figures, The Grange’, 1875, watercolour over pencil on paper on cardboard, 24.7 x 35.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

This exhibition is chronological and the art of Merric’s parents and brothers are on display in cabinets and on the walls of the first room. Merric’s father, Arthur Merric Boyd (1862-1940), was born into the military Boyd and landowner Martin families, while his mother, Emma Minnie à Beckett (1858-1936), inherited status and money from the judiciary à Beckett and beer-brewing Mills families. This meant that the Boyds were able to live a life of leisure in relative comfort throughout the nineteenth century. In 1866 the family moved to The Grange in Harkaway, Victoria, and Emma’s painting above depicts the late Victorian drawing room shaded by a verandah with a view looking south over the garden to the bush beyond. The couple are presumed to be Emma’s sister Emily and her fiancé. This painting is proof of Emma’s proficiency as a watercolourist. Between 1919 and 1922 Emma Minnie, Arthur Merric and their daughter Helen lived in a house they built beside Open Country. Named Tralee, it still survives, at 12 Wahroonga Crescent.

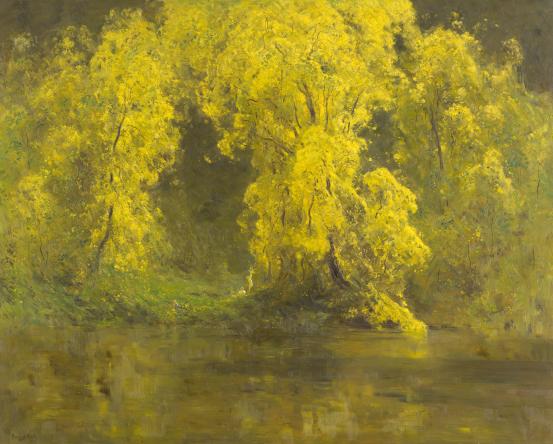

Penleigh Boyd, ‘The Breath of Spring’, 1919, oil on canvas, 122.0 x 154.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The first room also includes remarkable landscape etchings, watercolours and oils by Merric’s brother, Penleigh Boyd (1890-1923). Penleigh bought land at Warrandyte on the Yarra River where he designed and built a home and studio which he called ‘The Robins’. While serving in France during the First World War, Penleigh was gassed at Ypres and sent home as an invalid in 1918. He retreated to ‘The Robins’ and produced both bleak and celebratory landscape images in oil and watercolour. ‘The Breath of Spring’ is featured on one wall of this room—the evocative beauty of golden wattle in bloom would have been a welcome sight for Penleigh after witnessing the devastation of trench warfare. Tragically, at the age of 33, Penleigh was killed instantly in a car accident near Warragul, Victoria, on 28 November 1923.

Yosl Bergner, ‘The village on fire’, 1940, oil composition on board, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The second room, with its black walls and subdued lighting, features grim paintings and sketches produced during the Second World War by Merric’s first son, Arthur Boyd (1920-1999), John Perceval (1923-2000; in 1942 he moved to Open Country and in 1944 married Arthur’s youngest sister Mary, who later married Sidney Nolan), Albert Tucker, and émigré artist, Yosl Bergner (born 1920). A Viennese-born Jew, Bergner spent his childhood in Warsaw but was forced to flee Nazi Europe, arriving in Melbourne in 1937 where he met Arthur Boyd. The homeless Bergner was welcomed at Open Country. Identifying with the dispossessed, and hearing of European cities being destroyed by war, Bergner began to paint a series of paintings that conveyed the devastation and desperate plight of people forced to flee their homes during war. Bergner introduced young Melbourne artists such as Perceval, Tucker, Arthur Boyd, and Yvonne Lennie (whom Arthur married) to elements of European Expressionism, Surrealism and Social Realism. Being pacifists and passionate humanitarians, the Boyd circle of artists responded and produced paintings that reflected universal suffering. John Perceval’s dark and confronting ‘Survival’ and ‘Soul Singer at Luna Park’, both painted in 1942, hang adjacent to Bergner’s ‘The village on fire’ (1940).

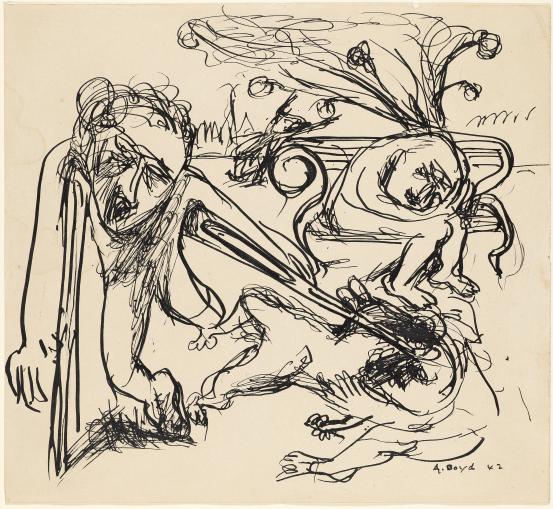

Not only was Arthur Boyd influenced by Bergner’s grim images of human plight, but he was also affected by his joyless experience of the Depression that projected into the Second World War. Between 1942 and 1946 he produced a disturbing series of drawings and paintings that conveyed a range of social and psychological realities: conflict and order, cruelty and compassion, sin and innocence, passion and resignation. Arthur’s reed pen and ink drawings of 1942 reference mutations of cripples, floating figures, entwined lovers and strange hybrid animals in industrial or inner-city landscapes. Arthur depicts them with irony, and some even convey a sense of frivolity.

Arthur Boyd, ‘Figure with crutches, fallen figure and figures on bench’, 1942, reed pen and ink, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

One of Arthur Boyd’s reed pen and ink drawings on display in this ‘War’ room is ‘Figure with crutches, fallen figure and figures on bench’ (1942). The figure on crutches is thought to be his friend and brother-in-law, John Perceval, who was afflicted by infantile paralysis. Boyd gives the figure a carefree energy that transforms the awkward movements of someone who clutches crutches in a dance-like movement. In Arthur’s painting, ‘The Weathercock’ (1944), which is hanging on the wall next to his pen and ink drawings, there is a similar image of a strange man on crutches smiling as he rides a dog-like creature—they are invading the privacy of two lovers who are huddling under the gnarled and windswept tree. A reptile-looking beast dances on two legs with a three-armed man. This is a barren landscape with an intense sun, and yet there is an evocation of winter. Australia’s sense of isolation at this time added another dimension to Arthur Boyd’s expressionist-surrealist imagery.

Arthur Boyd, ‘The Weathercock’, 1944, oil on muslin on (board), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Emerging from the darkness, the next room is well-lit with walls painted white, setting off the pottery produced by Arthur Merric Boyd (AMB) Pottery. In 1944 Arthur Boyd, John Perceval and German-born philosophy student Peter Herbst established AMB Pottery, named after Arthur’s beloved grandfather. Herbst famously commented that they “avoided ‘good taste’ like the plague”. The AMB potters and artists worked from a shop not far from Open Country at 500 Neerim Road, just across from the Murrumbeena Station. When Herbst left for Oxford in 1950 to further his academic career, potter, painter, naturalist and conservationist Neil Douglas, who had already been working at AMB Pottery, replaced Herbst as a partner. Douglas created his distinctive, idiosyncratic pieces that combined a feathery but skilful painting style with simple thrown forms.

Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery, Earthernware Bowl, 1947, Neil Douglas(decorator), John Perceval (potter)

Merric’s other sons, Guy and David Boyd moved to Sydney and set up a pottery studio in 1946—Guy was primarily a sculptor. David, a painter and sculptor, met his wife Hermia Lloyd Jones at the studio; later, they developed their own potteries in Sydney, England and France. While his brother, Arthur, often seemed shy and withdrawn with a bleak imagination, David was gregarious with an obvious intelligence and outgoing charm. There are displays in this room that feature David and Hermia’s unique pottery and sculptural forms.

Arthur Boyd, ‘Christ carrying the Cross’, 1946-47, oil on canvas, 86.7 x 100.6 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

During the mid-1940s, Arthur Boyd was influenced by the Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Brueghel, particularly Brueghel’s relocation of biblical or mythical events into chaotic contemporary settings. Merric and Doris were deeply religious and the Boyd family spent most evenings at Open Country reading the Bible. In Arthur Boyd’s painting, ‘Christ carrying the Cross’, Christ is bearing his burden as he struggles to make his way through what looks like a Victorian country agricultural show, crowded with people, animals and tents. There is even an Australian Rules football oval on the horizon. The Brueghelesque mob-like composition represents Boyd’s favourite themes of the confusion of life, love and death. We see lovers embracing beneath the dead tree on the left, a Bosch-like nude riding backwards on the back of a man, and death-masked figures crouching beneath her as if from a German Expressionist painting. Art critic Robert Hughes described the scene as “an arena of maddness, where innocence and experience grappled.”

Arthur Boyd, ‘David and Saul’, c. 1952, glazed earthenware, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

During the 1950s Arthur produced an impressive series of luminous glazed earthenware tiles and chunky Picasso-inspired figurative hand-modelled sculptures. Boyd used mythological and biblical stories and characters as his subject matter. The terracotta sculpture, ‘David and Saul’ (c. 1952), depicts the complex relationship between Old Testament characters of King Saul and David. Saul was a fine leader but he became increasingly moody and jealous of David’s popularity. The expressive work shows David the shepherd playing his lyre to comfort the king in his disturbed mental state. In a tender paternalistic moment Saul lays his hand on David’s head. This is a masterpiece of pathos, perhaps symbolising Arthur’s sadness as his father became increasingly debilitated by epilepsy. The firing, if only one, would have been long and slow. Arthur Boyd wrote about the moment he opened the door of the kiln to remove the sculpture:

‘When I took it out it was still hot. It was a most marvellous feeling … I’ll never forget it … a painting doesn’t have anywhere near the impact of pulling something out that has been almost purged by being through fire … It is a pure object and it is changed. It’s formed in the fire and so the surprise is marvellous.

Arthur Boyd, ‘The wheatfield’, 1948, Harkaway, Victoria oil on composition board, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The last room in this exhibition displays a decade of Arthur Boyd landscape paintings dating from 1948. While living with Yvonne and daughter Polly at The Grange, the old family home in Harkaway, and working on the religious murals commissioned by his uncle, the writer Martin Boyd, Arthur seems to have found a post-war tranquillity. This is evident in the gentle undulating hills of the Berwick countryside depicted in his 1948 painting, ‘The wheatfield’, which expresses a new-found contentment away from the busy Murrumbeena AMB Pottery studio. Arthur was also exploring thinned oil paint to create a translucency that mimicked that of ceramic glazes.

It is equally apparent that Perceval had found a new style of painting in the 1950s that conveyed a feeling of release. His paintings of life at the run-down sea front and dock area in Williamstown are carefree, even quirky—a progression from the linear and sombre work of the early 1940s. There is an exuberance in his brushstrokes and use of primary colours, which enhance the movement and bustle of these seaside scenes.

As the artistic careers of Arthur Boyd and John Perceval developed in different directions, and they moved away from Open Country, their involvement in the AMB Pottery declined, and ceased altogether in 1958 when the partnership was dissolved. Soon after Merric’s death in 1959, Arthur and Yvonne departed Australia with their children. By 1964 it was clear that Open Country had run its course and it was sold. The house and outbuildings, including architect Robin Boyd’s modernist studio designed and built for his cousin Arthur in 1938, were bulldozed and a drab block of flats built in their place.

***

The heart of the house at Open Country was the Brown Room, a sitting room where the Boyds and their friends gathered to talk about their art, design pottery, sing, play and listen to music. Peter the dog would curl up at Merric’s feet and Old Testament stories were read to each other; this is where émigrés fleeing from Europe felt welcome and safe.

There is a darkened room at the end of the exhibition that aims to emulate the Brown Room. Photographs of Open Country that capture the interaction between the Boyds and their friends are projected onto the walls (mainly photos taken by Albert Tucker). It is worth taking time to sit and reflect upon this important chapter in Australian art. A few comfy chairs, a table and chair, and a Boyd pot or two scattered around the room would enhance the visitor’s understanding of Open Country even more.

Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery, Arthur Boyd (decorator), Decanter set, 1948, earthenware, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The vessels and figures produced by Merric and Doris Boyd from the 1910s onwards, and the domestic and decorated pottery made by their children, their spouses and friends from the 1940s, provided incomes that enabled them to further their painting careers beyond the Outer Circle. Open Country was a significant place of art during the difficult period of two world wars and their aftermath.

A visitor to Open Country in 1955 described its charm:

. . . I at once fell under the spell of that seemingly enchanted place, sinking into the cheerful muddle of papers, pots and naked babies in which the only recognisable item of furniture was a high fidelity gramophone dispensing early Italian harpsichord music into the intermittent din.”

The exhibition runs until 1 March 2015