Twelve skulls, wrapped with pink silken thread, are suspended from the ceiling in the first room of the contemporary art exhibition, ‘Animate/Inanimate’, currently on show at the TarraWarra Museum of Art (TWMA) near Healesville. One skull has a spade in its mouth, another has partly morphed into a trumpet, and an iron is slammed into the ‘face’ of another— these inanimate skulls have been brought to life by everyday hand-held objects, colour, and luminosity. This work of art by Chinese artist, Lin Tianmiao (born 1961), is called Reaction (2013): a response to the negative impact of politics and rapid social change on lives and the environment in China. More broadly, Reaction evokes many themes relating to human experience across the globe: the toil of daily work that often deadens the human spirit; the rejuvenation of the spirit through creative pursuits; the violence in our society; the association of women with the activity of binding and weaving; embalming as a means of preserving the body for the afterlife. Lin explains her use of bones in her art:

I believe that the bone is the only perfect object left in the world. Bones do not have the difference of hierarchy, culture, class, politics and social property between them. I use then casually to transform, continue, or reconnect with my artistic imagination . . . The most interesting thing about bones is they lead us to face our mortality.

In an intimate and darkened room just beyond Reaction, a video by U.S. artists, Jennifer Allora (born 1974) and Guillermo Calzadilla (born 1971), called Raptor’s Rapture (2012, image below), features flautist, Bernadette Käfer, attempting to play a pre-historic ‘flute’ carved from the wing bone of a griffon vulture (died out in the 18th century). In the background a living vulture oversees the musical ‘performance’, preening his wings and turning his head, as if he is adjudicating the proceedings, and sensing the role his ancestors played in the origins of sound and music. This bone, taken from a dead animal, is animated with sound yet destined to gather dust in a museum.

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, ‘Raptor’s Rapture’, 2012, single channel video projection, colour, sound. Photo courtesy of Allora & Calzadilla and Lisson Gallery, London.

In 2013 the TWMA celebrates its tenth anniversary with the launch of the inaugural TarraWarra International. TWMA director, Victoria Lynn, is curating this innovative show, which she hopes will expand the museum’s exhibition program by situating Australian art within a global context. Installations, sound works, sculptural elements and video works created by six contemporary artists (Australian and international) seek to grasp the effects of the changing nature of our planet on the natural world. Lynn tells me that she hopes viewers will engage with her idea that there is a “reciprocal exchange between the animate and inanimate”. How can this be? Lynn explains in the exhibition catalogue:

The works of art in the exhibition are inanimate in the sense that they are not breathing entities with a consciousness, yet they intonate a world of living things and their transition from life to death. Not only do the artists use creative methods by which an inanimate installation of objects, a video or film, creates a bond with living subjects; they also create sensations, energies or force fields that are imbued with qualities or states that we find in the natural world … The animate can be found in the inanimate. The inanimate becomes animated by the creative act.

Janet Laurence, ‘Fugitive’, 2013, installation view ‘Animate/Inanimate’, TarraWarra Museum of Art 2013, multimedia installation with video, dimensions variable. Photo: Mark Ashkanasy; courtesy of the artist and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne.

Dimmed lighting and veiled, cell-like structures create a haunting atmosphere in the central room. Viewers enter each cell through transparent mesh and look for the ‘spirit’ in the inanimate native Australian animal and bird specimens, many on loan from the Melbourne Museum. This work is called Fugitive (2013), the creation of Sydney-based artist, Janet Laurence (born 1949). Her art explores the impact that humans have on animals and their habitat. Laurence makes the comment that the inanimate museum specimens “exist somewhere between the living and the dead”; they have an “incredible presence and yet they’re long past”. The ‘up-close and personal’ shared spaces within these cells offer an immersive, meditative experience for the viewer. Acrylic sheets, mirrors and videos provide glimpses of animated, ghostly images of extinct or endangered animals; these spaces can be likened to small shrines.

This exhibition has a special relationship with the surrounding landscape of the Yarra Valley. According to Lynn, ‘landscape’ is more than a view: it has other meanings and histories—and so this exhibition, in this gallery, collaborates with the immediate landscape in a special way. Winter can be a quiet time in Healesville, but ‘Animate/Inanimate’ invigorates the area with art linking to the Healesville Sanctuary. On the first Sunday in July, August, September and October, there will be an opportunity to view the TWMA exhibition and then visit the Healesville Sanctuary; curators will talk about the art in the exhibition, and rangers will provide information about endangered Australian animals and birds living in an increasingly fragile habitat. Viewing inanimate and faded specimens, such as orange-bellied parrots lying motionless on flightless wings in Laurence’s art work, Fugitive,then being able to witness these endangered birds in brilliant colour and full flight at the Sanctuary, is a unique opportunity to come face-to-face with the plight of many native animals and birds.

Louise Weaver, ‘Hiding in Plain Sight’ (Witch Grass Nest) 2011-12, ‘Bird Hide’ 2011, ‘Time to Time’ 2013, installation view ‘Animate/Inanimate’, TarraWarra Museum of Art 2013. Photo: Mark Ashkanasy; courtesy of the artist and Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney.

There is a seamless flow from the room exhibiting Laurence’s ethereal work through to the adjacent, equally shadowy, room displaying five different sculptural elements by Melbourne-based artist, Louise Weaver (born 1966). Here I lost my way in the sense that I found it difficult to identify the idea of the inanimate linking with the animate in Weaver’s work. There is a wall label but it was not helpful; however, I understand that too much information can result in a narrowing down of the viewer’s interpretation and interaction with a work of art. I hear the sound of bird songs that the artist recorded in the Central District of Victoria, and my experience of viewing Weaver’s inanimate objects is immediately animated. Bird Hide (2011-12), made out of plastic and Japanese paper, invokes the man-made ‘hides’ created for passive viewing of living birds. The smaller sculpture, Hiding in plain sight (witch grass nest) (2011), hangs from the ceiling; it is inspired by the nests woven by male Weaver birds and Pacific Island costumes. I sense that I am in the presence of an abandoned nest that was once inhabited by busy, animated birds.

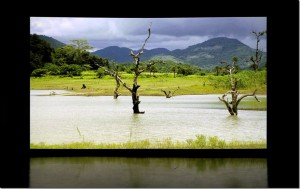

Rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, and the deadening effect on the landscape, has been an issue for artists since the first few decades of the 19th century. Amar Kanwar (born 1964), an artist based in New Delhi, has produced a film, The Scene of Crime (2011), that reflects upon the devastating impact of industry and mining on the human rights, agriculture, and livelihood of Adivasi (indigenous) groups in Orissa, India. In January 2006, fourteen Adivasi people were killed by security forces during a protest against Tata Iron and Steel Co Ltd. There was no justice. This film is narrated with text on screen through the persona of a woman who endured the loss of a loved one. Lynn suggests that Kanwar’s animated images are “entangled” with the inanimate, and that “our eye begins to look into the landscape for evidence; our eye becomes the woman’s search for justice”. When I entered the room to view the 42-minute film, the bow of a small timber boat is carrying the viewer slowly out of a rippling estuary towards the sea; the next frame emits the sound of wind, and we see its effect on the tall native grass; dead trees scar a lush landscape; a boy rides a bicycle along a path dwarfed by power lines. Amar Kanwar’s art explores the fraught exchanges between affect and effect; his film resonates with nostalgia, scorn, and—fear.

Amar Kanwar, ‘The Scene of Crime’, 2011, HD video installation, colour, sound,42 minutes; courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris.

The six artists in this exhibition may not necessarily have the same ideas, and their life experiences are culturally divergent, but their works of art connect as a collective meditation on the fragility of nature and human life across the globe. Art makes us think, but it shouldn’t tell us what to think. I drove away from the TarraWarra Museum of Art just as the sun slipped below the horizon and darkness descended—I had lots to think about thanks to this brilliantly conceived exhibition of contemporary art that dares to engage with the idea that there is a connection between the animate (endowed with life, living) and the inanimate (without life).

Post Script

In view of the fading animals

the proliferation of sewers and fears

the sea clogging, the air

nearing extinction

They are hostile nations (1971), Margaret Atwood

‘Animate/Inanimate’

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville, Victoria

Until 6 October 2013

Featured image: Lin Tianmiao, Reaction, 2013 ((detail: image of one part of a twelve part work), dimensions variable, coloured silk threads, stainless steel wires, synthetic skeletons and metal constructions.Photo by Yang Yuguang; courtesy of Lin Tianmiao, © Lin Tianmiao.

Thank you,

Victoria Lynn and the organisers for inviting me to the opening of ‘Animate/Inanimate’.

Katrina Grant, Editor of the Melbourne Art Network, for publishing my review:

Thank you Denise for your insightful review of the Animate/Inanimate exhibition. You said of the “Raptor’s Rapture” work: “This bone, taken from a dead animal, is animated with sound yet destined to gather dust in a museum.” It causes one to think of the work in a completely different way and demonstrates why reading a considered viewpoint about a work is always stimulating!

Thank you for your positive feedback, Eliza. This is a really significant exhibition.

Great review – thanks Denise. I haven’t seen the exhibition yet but will now make sure that I do. Interesting challenge of the animate/inanimate…

Many thanks for your comment, Helen. I know you will enjoy the exhibition – it certainly challenges our thinking on many levels!