Mont Sainte-Victoire is Cézanne’s mountain and I had to see it. On 13 October 2012 we’d spent too much time wandering through the charming town of Aix-en-Provence where Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) had lived most of his life. It was one of those perfect days in Provence: blue skies with a clear heat, but the autumnal sun was sinking towards the horizon, and Mont Sainte-Victoire is about a 30 minute drive east of the city. Finally, after walking through a shady pine forest from the carpark, we stood on a parapet and gazed in awe at the sublimity of the panorama before us.The austere mountain was enlivened with late afternoon Provençal sunshine; the valleys, forests and rocky outcrops below stretched out in sinewy layers of green, grey, mauve and orange. I see why Cézanne had puzzled over this mountain and struggled to represent what he saw. He painted Mont Sainte-Victoire, one of his favourite motifs, eighty seven times, trying each time to capture something beyond the visually transient, something beyond what the Impressionists sought to achieve.

Image 1. Paul Cézanne, ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire’, 1902-04, oil on canvas, 73 x 91.9 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Cézanne learned the techniques and theories of the Impressionists from his friend, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) but he chose to emphasise three-dimensionality and, simultaneously, a rhythmical two-dimensional pattern through geometric shapes rather than trying to capture the fleeting effects of natural light and atmosphere. Cézanne was a deceptively slow, cerebral worker, interested in the underlying structure of the landscape before him, whereas Vincent Van Gogh was hell-bent on capturing nature with his expressive colours and brushwork. Claude Monet’s predilection for painting water in all its forms and moods has often been noted; the reflecting surface of water was one of his favourite motifs. All three artists were searching for their own way of painting their visual sensations of nature. However, whereas Monet and Van Gogh created visual excitement and harmony with their complex fields of colour, Cézanne was more interested in the magnetic energy of shapes and colour—his abstract vocabulary was an exhilarating new approach to composition.

Standing before Mont Sainte-Victoire, I tried to imagine how Cézanne would have looked at this geological structure laid bare under the hot sun, and how he transformed what he saw into abstract visual notations. Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (Image 2) was painted around 1887 and is more representational than the later paintings. Traces of blue from the underdrawing remain visible and the clear emerald and olive greens in the foreground fade to softer blues and mauves of the mountain. He understood that cool colours recede, while warm ones advance. This suggestion of distance is also accentuated by the network of contours, buildings, roads and fences leading the eye to the mountain, and the overhanging branches pull it all together.

A few years before he died Cézanne painted Mont-Sainte Victoire (Image 1); the emphasis is abstraction and his intense response to every contour, shape and zone in the landscape. Rocks, buildings and trees are suggested by daubs of paint as opposed to being more realistically depicted. Cézanne experimented with colours that captured the sense of solidity, volume and depth, yet, the overall composition is still clearly representational: the looming mountain is a mix of various hues, assembled into a recognisable object.

Cézanne describes his method in a letter to his friend and fellow painter, Émile Bernard, on 15 April 1904:

Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, that is a section of nature. . . . Lines perpendicular to this horizon give depth. But nature for us men is more depth than surface, whence the need of introducing into our light vibrations, represented by reds and yellows, a sufficient amount of blue to give the impression of air.

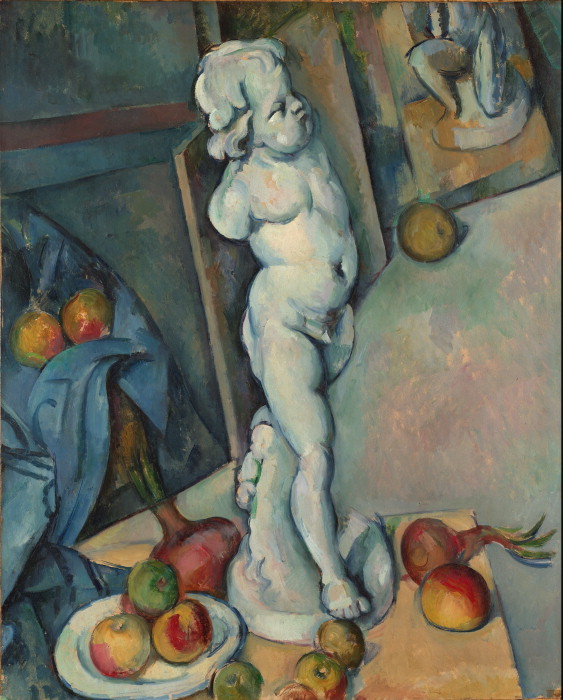

Image 3: Paul Cézanne, ‘Still life with Plaster Cupid’, c. 1894, 70.6 x 57.3 cm. London, Courtauld Institute of Art.

As can be seen in his still-life painting, Still life with Plaster Cupid (Image 3), Cézanne applied colour to create a three-dimensional effect. The colour blue was not only used for establishing an infinite sky, atmosphere, air between objects, reflected light, shadow and distance, but also for basic outlines. The model of the cupid featured in this painting is still standing on a table in his studio, which we visited in Les Lauves on the outskirts of Aix-en-Provence. The studio is a tribute to Cézanne: his palette, brushes, and still-life objects remain as if he had just closed the door to climb up Lauves hill to take in the view of Mont Sainte-Victoire (the view has since disappeared due to modern development).

The late paintings of Paul Cézanne proved to be of a paramount importance to the emerging modernists, who sought to liberate themselves from the rigid tradition of pictorial depiction. There’s been much written about this intense man from Aix who was the conduit from Impressionism to Modernism, but a new book on Cézanne by Alex Danchev, Cézanne: A Life, combines biography and details of his art practice with the opinions of Cézanne by an array of painters and writers, such as his boyhood friend Emile Zola, DH Lawrence and EE Cummings; not everyone was complimentary. This multiplicity of viewpoints presents a complex Cézanne that gives weight to his belief that “All my compatriots are arseholes beside me”.

Hi Denise,

Thanks for posting this lovely article and photos. I am headed to France this Spring- I’m a landscape painter. I am thinking of painting Montagne-St-Victoire, and was looking for the best place to paint it from. Do you recall where you parked to take this picture? Is there a public park?

Je vous remercie d’avance. (thanks in advance…)

Cordialement,

Matthew Lee

Hi Matthew,

How wonderful to paint this iconic mountain! We drove about 10 kms east of Aix-en-Provence and ended up on a narrow, winding road that led us to a car park. We then walked though a beautiful forest to the viewing area – breathtaking! What a lovely shady vantage point to paint Cezanne’s mountain.

Good luck finding this place.

Best wishes,

Denise