A sense of timelessness pervades the circuit walk at Stourhead garden in Wiltshire, England. This is a sublime place of beauty where nature has become art, ordered and arranged by humans. The last time I experienced this eighteenth-century landscape garden was on 28 October 2012 when rain tumbled softly, unhurried in the calm weather. Autumn colours were heightened by the wet foliage and the near-perfect reflections in the lake added a third dimension to the picturesque views across to classical and Gothic buildings. Towering trees of gold and green, and fragile canopies of crimson maples, framed the lake and set the woods alight with colour.

In 1741, English banker Henry Hoare II (1705-1785), inherited Stourhead with its Palladian house and surrounding estate. He designed a landscape garden for reflection and stimulation—a means of returning to the Italian Classics after his Grand Tour of Italy. Hoare dammed the head of the river Stour to create an artificial lake in the basin, around which he built a series of classical temples such as the Temple of Apollo, the ultimate destination of a mythical journey. The mist that shrouded the temple during my visit in 2012, as I viewed it across the lake, added a magical sense of the past.

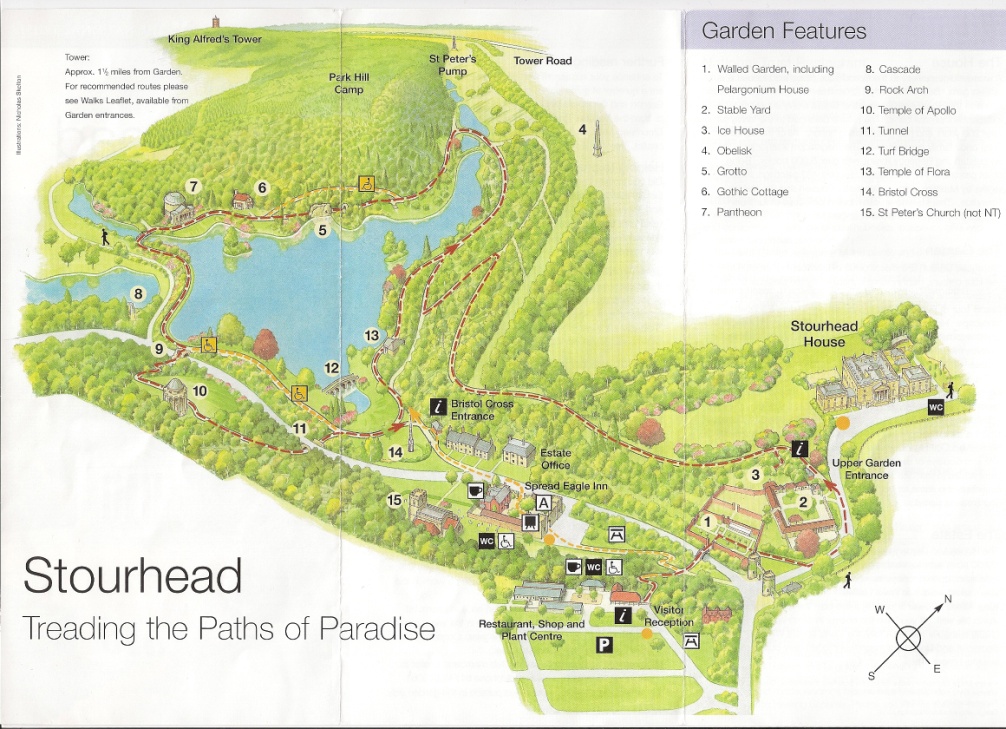

Many garden art historians argue that the pictorial circuit at Stourhead narrates, in part, Virgil’s poem, Aenead: a myth featuring the Trojan hero, Aeneas, who, after the fall of Troy, made a long voyage around the Mediterranean by way of Carthage, finally landing in Italy where he became the founder of Rome. The best way to experience Hoare’s original vision is to follow an anti-clockwise route around the lake so that Aeneas’ journey is reproduced allegorically in the garden, mingled with motifs from classical mythology. The story can then be revealed in the correct order with calculated views. Henry Hoare intended that his landscape garden satisfied the eighteenth-century invention of ‘stations’ for the ‘picturesque tourist’—places where the best authorised vistas could be viewed.

Perfectly paralleling Aeneas’ descent in to the underworld, the path descends to a grotto containing statues of a sleeping nymph alluding to the cave of nymphs at the place where Aeneas lands in North Africa. Although the grotto emulates a dark and cold cave, a ‘window’ offers a vista across the lake to the Temple of Apollo situated high on the hill. Grottoes were popular in Italian Renaissance gardens where the cool interior was a welcome retreat from the summer heat. In another part of the grotto there is a statue depicting the god of the river Tiber who is pointing to the building further around the garden. This is a model of the Pantheon, formerly called the Temple of Hercules, where Aeneas sought an alliance with the Arcadians. The steep path out of the grotto marks Aeneas’ difficult journey back to the upper regions.

Before reaching the grand classical architecture of the Pantheon you will pass the picturesque, rusticated Gothic cottage which is situated half way around the garden, a great place to revive and take in the view across the lake to the Palladian Bridge and the Temple of Flora. Both times I visited Stourhead, in the cold months of winter and autumn, the cottage was decorated with fir cones and foliage from the trees on the estate. During my last visit hot drinks were being served and the fire was burning brightly. Very welcome!

Before reaching the grand classical architecture of the Pantheon you will pass the picturesque, rusticated Gothic cottage which is situated half way around the garden, a great place to revive and take in the view across the lake to the Palladian Bridge and the Temple of Flora. Both times I visited Stourhead, in the cold months of winter and autumn, the cottage was decorated with fir cones and foliage from the trees on the estate. During my last visit hot drinks were being served and the fire was burning brightly. Very welcome!

Just a short walk from the Gothic cottage is a replica of the Pantheon in Rome; this building is the largest on the Stourhead circuit. Inside, niches display statues from Greek mythology including Bacchus and Diana the huntress, but they are dominated by Michael Rysbrack’s marble statue of Hercules, which was installed in 1757.

Claude Lorrain, ‘Landscape with Aeneas at Delos’, 1672, oil on canvas, 100 x 134 cm, National Gallery, London.

It is possible that due to Hoare’s interests in seventeenth-century landscape paintings, the garden at Stourhead was inspired by a combination of romanticised images of Arcadian landscapes and picturesque views given form through the imagination of painters such as Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain (the Italianised French painter) and Gaspar Duchet, with specific reference to the classical world. Claude Lorrain’s Landscape with Aeneas at Delos (1672) depicts Aeneas (in short red cloak) standing in a Doric portico facing the Temple of Apollo, which recreates the original appearance of the Pantheon. The composition of the painting evokes Aeneas’ Trojan past and his future as the founder of Rome. Of course, it may be a romantic notion to imagine that the Stourhead garden is a copy of a painting; however, one can’t help feeling that the Claude painting shaped Henry Hoare’s visual imagination.

The spectacular Tulip tree growing near the five-arched stone Palladium Bridge (purely ornamental) was planted by Sir Henry Colt in 1791 and stands majestically on the edge of the lake. The physicality of this sculptural tree evokes the passing of time, especially when the yellow leaves are falling. I always think of the garden at Stourhead as so finely tuned to nature and the living contours of hill and lake that it is hard to tell what is nature and what is art.

Henry Hoare infused his personal landscape garden at Stourhead with Gothic elements and the spirit of the Enlightenment and the Classics, leading the visitor on a mystical journey along his man-made paths. Even though the original intention and meaning of the garden may be unknown to the modern visitor, the experience cannot be diminished. This immersive and peaceful garden will continue to delight and paint the seasons with nature for as long as there is someone to care for it.

Alexander Pope, eighteenth-century poet and gardener, wrote in his Epistle IV to Burlington (1731), that the “genius of the place” (the existing physical conditions of the site) needs to be consulted before there is a creative response by the gardener. This inspired process results in a perfected form of place-making, just like the garden at Stourhead.

To build, to plant, whatever you intend,

To rear the column, or the arch to bend,

To swell the terrace, or to sink the grot;

In all, let Nature never be forgot.

But treat the goddess like a modest fair,

Nor overdress, nor leave her wholly bare;

Let not each beauty ev’rywhere be spied,

Where half the skill is decently to hide.

He gains all points, who pleasingly confounds,

Surprises, varies, and conceals the bounds.

Consult the genius of the place in all;

That tells the waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’ ambitious hill the heav’ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the vale;

Calls in the country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks, or now directs, th’ intending lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

Love it Denise! Thanks.

Brought to mind: “True wit is Nature to advantage dressed.”

Have you been to Stowe?

Barrie

Thanks Barrie, I have Stowe on my very long list of gardens to visit!

Thank you Denise. You really took me there, and the poem is profound and beautiful. I love the line, ‘consult the genius of the place’. I think it applies to child rearing as well.

Nita

I’m glad you enjoyed my post on Stourhead, Nita. I love this peaceful place of art. It has such beauty.