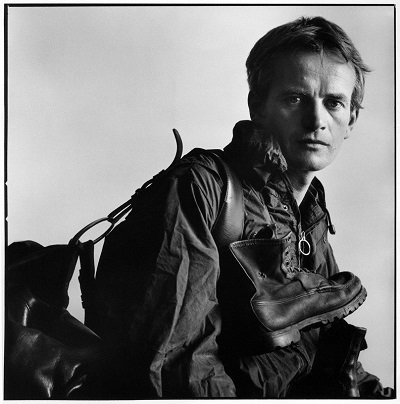

Travel writing often ends up being fantasy. The idea of the writer-artist as an independent traveller embodies a romantic notion that the source of his or her inspiration is an unrestrained inner life. English travel writer, Bruce Chatwin (1940-89,) was a post-Vietnam-War traveller, content to travel alone and live in ‘native’ standards of comfort. His writing style is as intoxicatingly unrestricted as his solitary wanderings. Chatwin constantly shines an inquisitive light on ancient nomadic cultures, especially those located in desert regions. He espouses that freedom of the soul requires freedom from the vulgarity of modern culture. We find out in Chatwin’s The Songlines (1987) that he quit his job in the ‘art world’ and went back to dry places: alone, travelling light. He proposes that . . . it is easier to understand why greener pastures pall on us; why possessions exhaust us.

Songlines is a reflection of Chatwin’s nomadic travels across Central Australia and the labyrinth of invisible pathways which meander all over Australia, known to Europeans as ‘Dreaming-tracks’ or ‘Songlines’; to the Aboriginals as the ‘Footprints of the Ancestors’ or the ‘Way of the Law’. Aboriginal Creation stories tell of ancestors wandering across the Australian continent in the Dreamtime creating songlines: singing out the names of the flora and fauna as they walked—birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterholes—and so singing the world into existence. Chatwin is accused of being a traveller who appropriated post-colonial cultural knowledge, especially when he wrote his own Aboriginal Creation myth, In the Beginning, even though it has a universal resonance. The story begins: In the Beginning the earth was an infinite and murky plain and ends: The Ancients sang their way all over the world. They sang the rivers and ranges, salt-pans and sand dunes . . . they left a trail of music. They wrapped the whole world in a web of song; and at last, when the Earth was sung, they felt tired. . . Some crept away to their ‘Eternal Homes’, to the ancestral waterholes that bore them. And they all went back in.

Bruce Chatwin didn’t believe in the ‘travel book’ full of facts. He was more interested in blending his ideas and travel experiences with fiction, history and myth. To call it [Songlines] fiction isn’t strictly true, but to call it nonfiction is an absolute lie, barked Chatwin. Nicholas Shakespeare, Chatwin’s biographer (1999), believes that Chatwin tells not a half a truth but a truth and a half. As such, Songlines is a literary phenomenon, one I often use as an example to those writers who are interested (or not) in blurring the line between fiction and document. Of course, doing so may attract criticism that many inexperienced writers cannot bear.

For Indigenous Australians, the songline defines the relationship between the individual and the landscape, and is a sign of his or her inalienable ‘ownership’ and deep communion with sacred ancestral territory. Although Chatwin’s idea that nomadism characterises the human psyche captures the imagination, his writing fails to capture the essence of the Australian desert landscape. In this regard, Aboriginal artists such as Muni Rita Simpson succeed where Chatwin fails. Muni was the first Martu artist to paint an aerial view of the remote Great Sandy, Little Sandy and Gibson Deserts of Western Australia. In 2008 Muni painted Yimiri (pictured above), which depicts Yimiri, the freshwater soak (yinta) within one of the saltwater lakes, with pathways or songlines of their ancestors snaking across the canvas in dotted lines evoking footsteps. This is more than just an aerial view of a desert landscape with life-sustaining waterholes; it embodies Muni Rita’s spiritual connection to the land and her memories of a nomadic life as a child.

Muntararr Rosie Williams and Yikartu Bumba, Yimiri, 2009, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 296.6 × 125.3 cm, Punmu, Western Australia, owned by NGV.

When Muni died in November 2008, her younger sister, Muntararr Rosie Williams, and fellow artist Yikartu Bumba, painted their version of Yimiri as homage to Muni and the way she showed them how to paint their Country. The 2009 painted version (above) depicts two small freshwater soaks painted in vivid blue surrounded by lush green within a vast white space representing a dazzling salt lake (part of the Percival Lakes). Two lone trees, dwarfed by the vast expanse of white, are rooted onto a horizontal thread of red around its perimeter, suggesting living creatures and bush tucker. The absence of any horizon line expresses the artists’ spatial affinity with the land—their ancestral place. Tracks along the sandhills surrounding the salt lake are painted in brightly-coloured horizontal lines, creating a visual vibration of spiritual resonance. Judith Ryan, senior curator of Indigenous Australian art at the National Gallery of Victoria wrote about these two versions of ‘Yimiri’: “Both of these horizontal views eternise the three artists’ cherished cultural memories of walking around Yimiri in pujiman [nomadic, bush] days and clambering over the surrounding tuwa [sandhills] to reach the fresh water.” (Judith Ryan, Living Water: Contemporary Art of the Far Western Desert, 2011).

In Geoffrey Blainey’s ground-breaking book of 1975, The Triumph of the Nomads, he surmises that for nomadic Aboriginals, possessions were a burden . . . In moving around they were not creatures of whim but of purpose; their wanderings were systematic, not aimless. In fact, Blainey calls their nomadic existence, pilgrimages: the land their chapel, the hills and creeks their shrines, and the animals, plants and birds their religious relics.

In Songlines, the idea of the nomad creating Dreaming trails through his or her own words while walking through the dry places from one waterhole to another, appealed to Chatwin, the lone pilgrim. Many of his travel stories and recollections of his studies in linguistics, archaeology and anthropology, mainly addressing the nomadic existence, occupy nearly one-third of the book. For example:

. . . in the East, they still preserve the once universal concept: that wandering re-establishes the original harmony which once existed between man and the universe.

He also includes quotes from proverbs, spiritualists and philosophers:

Our nature lies in movement; complete calm is death. (Pascal, Pensees).

On a broader level, Songlines explores cultural differences and the nature of quests or pilgrimages that attempt to access sacred and ancient knowledge, linking travel, language and territory. What Chatwin is telling the reader is that humans will not only survive, but also find freedom for their souls from the restrictions of ‘civilised’ life if they return to a nomadic life. He believes that this is not a fantasy of travellers or romantic poets or ‘primitivist’ anthropologists, but a reality rooted in man’s earliest experience of the earth. Chatwin sums up his sublime, universal vision of songlines:

I have a vision of the Songlines stretching across the continents and ages; that wherever men have trodden they have left a trail of song (of which we may, now and then, catch an echo); and that these trails must reach back, in time and space . . .

(Featured painting: Muni Rita Simpson,’Yimiri’, 2008, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 125.0 × 295.4 cm, painted in Punmu, Western Australia, owned by NGV)

I think this is a superb account Denise.

Thanks

Thanks Barrie (and Happy New Year to you).

cheers

Denise