Leaves were falling and London was wearing a mantle of fog on the morning of Monday 22 October 2012. Autumn leaves brought to mind two exquisite paintings, ‘Autumn Leaves’ (1856) and ‘Mariana’ (1851), by John Everett Millais, one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). So it made sense to head for the Tate Gallery, situated on the banks of the Thames, and revisit, in the flesh, the evocative (and provocative) works which transformed Victorian British art from the middle of the 19th century to its close.

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, promised a fresh look at the work of Pre-Raphaelite artists who, we are told, “rebelled from artistic orthodoxies” (more on that later). Staging this exhibition during autumn and running it until mid-winter (13 January 2013) gives the British a chance to escape the gloomy weather and immerse themselves in the vibrant palette, sunny landscapes and engrossing narratives of the art of the Pre-Raphaelites. The show sets out to challenge the stigma attached to Pre-Raphaelitism as an insular, conservative, retrogressive and escapist ‘Victorian’ art movement by re-branding this art as avant-garde and modern (for the times). There are more than 150 works in different media, including paintings, sculpture, photography and the applied arts. It is an ambitious effort by the curators.

The exhibition begins in the traditional way with a dozen works of art in the first room intended to embody the genesis of the PRB art movement and the aspirations of the young founding artists. The room label, ‘Origins & Meaning’, disappoints – how dreary! The first sentence in the wall text fails to pack a punch: “The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in September 1848 at a turbulent time when the ruptures in the new industrial society became visible.” Yes, but who founded the PRB and where was its centre of activity? What “ruptures”? The next sentence is just as confusing: “Hunt and Millais witnessed a Chartist demonstration.” Too bad if you haven’t heard of Hunt and Millais, or the Chartists.

So, just in case you don’t know, of the seven founding PRB artists there were three possessing major talent, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais; 21, 20 and 19 years old respectively. They signed their early work ‘PRB’ as a secret code to express their youthful rebellion against the deadening traditions of the art establishment during the mid-19th century. The wall text ends with: “They adopted the freshness of early-Renaissance art, but their work is essentially modern.” This needs clarification. Early-Renaissance art (roughly 1400 to 1479) is often considered to be the first modern art movement in Western art as it embodied a new vitality with convincing spatial settings, and even shadows in the sun. While they looked back to this time before Raphael (who was most closely associated with the Academic tradition), the Pre-Raphaelite artists were not necessarily nostalgic but favoured a unique combination of medieval romanticism and new realism. Inspired by the theories of art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900), who urged artists to “go to nature”, the PRB also created works dealing with religious, social and political themes, love, death, and subjects from literature and poetry.

My eye was immediately drawn across the room to the extraordinary painting, ‘Isabella’, by Millais (Image 1) which he began painting in the founding year of the PRB (1848). This is one of the works I had hoped would be on loan from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. It is quintessential ‘early Pre-Raphaelite’ and launched the PRB with its medieval themes, psychological intensity, flattened forms, brilliant colours and sharp relief. It is also evident that the young artists were eager to explore contemporary social, moral and political issues through their art such as the widening gulf between the poor and the burgeoning middle class. This is a medieval Italian tale about the daughter of a rich merchant family who loved a penniless young clerk. Isabella’s creepy brothers (such as the one on the left annoying Isabella’s dog) murder her unsuitable lover. But check out the ‘snotty-nosed’ row of bourgeois types on the other side of the table next to the two lovers. This is a painting about love, death, class division and secrets; a drama full of resonance with the Victorian period. In 1818 John Keats immortalised this story in his poem of the same name. Read it to find out the very quirky ending …

We discover that the Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by the Gothic Revival architect Augustus Pugin (1812-1852) who looked back at medieval styles, and the German Nazarene painters who rebelled against the Vienna Academy in 1809. The promise of ‘avant-garde’ isn’t immediately evident but visitors would be getting an idea of what motivated these young Pre-Raphaelites.

The next room labelled ‘History’ (too broad) introduces the connection between the PRB and the acclaimed poets of the time. In particular, the Pre-Raphaelites engaged with the poems of Alfred Tennyson, creating a unique artistic vision of the lone figure of a contemplative woman, gazing not at the viewer but inwardly—an enclosed and idealised woman. The pièce de résistance of this isolated woman drawn from a poem by Tennyson will come at the end of the exhibition in a magnificent painting by William Holman Hunt. ‘Mariana'(featured image above) hangs in this ‘History’ room and was painted by Millais in 1851. The woman is the character of Mariana in Shakespeare’s ‘Measure for Measure’ who is rejected by her fiancé, Angelo, after her dowry was lost in a shipwreck. The following lines from Tennyson’s poem, ‘Mariana’ (1830), are referenced:

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Mariana has been working at her embroidery and pauses to stretch her back. Her longing for Angelo is suggested by her pose. This painting is not only rich in colour (the blue of her dress is vibrant) but dripping with symbolism. Autumn leaves on the carpet mark the passage of time and the stained-glass window depicts the Annunciation, contrasting the Virgin’s fulfilment with Mariana’s loss. The mouse in the right foreground is Tennyson’s mouse that from the crevice peer’d about.

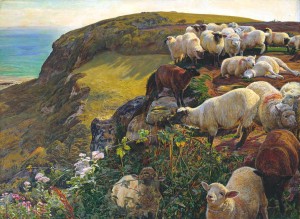

Now to ‘Nature’. This room reflects upon the Pre-Raphaelites commitment to truth to nature and its many elements. Alexander Munro’s sculpture of boy and dog, ‘Young Romilly’ (1863), with its shining white marble surface and naturalistic detail effectively conveys wind and sunlight. Ruskin raved about William Holman Hunt’s 1852 landscape painting, ‘Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep)’, (Image 2) in one breathless sentence: “It showed to us, for the first time in the history of art, the absolutely faithful balances of colour and shade by which actual sunshine might be transposed into a key in which the harmonies possible with material pigments should yet produce the same impressions upon the mind which were caused by the light itself”. Parallels can be seen between the precision of Pre-Raphaelite paintings and the new medium of photography, yet the PRB valued photography more for its creative potential: cropping, flattening of forms, tonal qualities, and focus. At the same time, photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) expanded the expressive range of the camera, creating a distinctive Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic in her photography (mainly portraits). Her photographs are included in the exhibition.

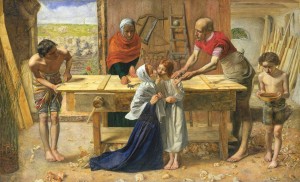

Semi-religious themes which incorporate Victorian life (hung-up on morality and salvation) are covered in the large ‘Salvation’ room. Here I see the avant-garde label of Pre-Raphaelite art starting to make sense. The PRB sought to make the moral and humane teachings of the Bible relevant in order to emphasise suffering and compassion in this world rather than redemption in the next. They painted scenes from the Bible with unprecedented realism. Millais’ ‘Christ in the House of His Parents’ (Image 3) offended many Victorians because the Holy Family is depicted as an ordinary family working to make a living; Joseph is balding and Charles Dickens described Millais’ Virgin Mary as “horrible in her ugliness”.

The unfinished painting, ‘Take your son, sir’ (1851-57), by Ford Madox Brown (Image 4) has been subject to conflicting interpretations but is most likely a celebration of Victorian parental pride. The woman’s voluminous white dress is incomplete, giving the impression that the baby she holds is emerging from her ‘womb’. Close inspection reveals that this is a contemporary scene, but not necessarily one of marital bliss . Is this baby illegitimate and being held out to the viewer? The circular mirror behind her head looks like a halo yet it reflects the figure of a man – perhaps she is appealing to the baby’s father: Take your son, sir! Madox Brown could be unveiling the ugly underbelly of a society in which women were often treated unfairly. The subject matter and lack of finish could certainly be considered avant-garde . And now to beauty.

The wall text in the room labelled ‘Beauty’ explains that “around 1860, the Pre-Raphaelites began to turn away from the realist engagement with nature, society and religion to explore the purely aesthetic possibilities of picture-making. Beauty came to be valued more highly than truth…” Here we see the clash of the idealised ‘Victorian angel’, virginal and beautiful; and the femme fatale, a figure of danger and allure. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘The Beloved (The Bride)’, painted 1865-66 (Image 5), embodies this concept of the power of female beauty. The black boy was apparently intended to add an element of exoticism, but his dark face also provides an effective contrast with the pale complexion and auburn hair of the bride. In the painting, ‘Autumn Leaves’ (1855-6), by Millais, the triangular arrangement of the four girls, who cast deep shadows, is anchored by the central pile of autumn leaves. Our senses come alive; we can smell the burning leaves and hear the crackle of the fire as the sun sets. Ruskin would have approved of this beauty embodied in the exquisite twilight. I used to feel sad before this painting but the reassuring audio voice explained that we should not feel melancholic —instead, the painting should help us understand the need for change throughout our lives.

Image 6, William Morris, ‘Peacock and Bird carpet’, 1885-90, William Morris Gallery: London Borough of Waltham Forest

The final two rooms, ‘Paradise’ and ‘Mythologies’, are largely devoted to the late 19th century metamorphism of Pre-Raphaelitism into the Aesthetic (‘art for art’s sake’) and the development of the Arts and Crafts movement, even Symbolism. In these rooms we meet second-generation Pre-Raphaelites: the decorative arts designer, William Morris, and the narrative painter, Edward Burne-Jones who were both inspired by medievalism. Burne-Jones’ poetic scenes, soft outlines and deep shadows remind me of Giorgione; the drapery suggests Fra Angelico.

William Morris established the decorative arts business, Morris & Co, in 1875 and in the 1880s he became a socialist advocating the revival of manual labour in the wake on the industrial revolution. His ideas about producing beautiful decorative objects and maintaining integrity in the workplace were very avant-garde. Morris created intricate designs such as the densely patterned ‘Peacock and Bird carpet’ woven by his company between 1885 and 1890. Morris & Co. also produced tiles, furniture, embroidery, stained-glass and textiles.

Image 6, William Holman Hunt, ‘The Lady of Shalott’, 1890-1905, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art: Hartford

William Holman Hunt’s spectacular masterpiece, ‘The Lady of Shalott’, (Image 6) ends the show. The legend of Elaine, the ‘Fair Maiden of Ascolat’, appears in Thomas Malory’s fifteenth century text about King Arthur and Camelot (Le Morte d’Arthur), and this legend is not only envisioned in Alfred Tennyson’s poem, The Lady of Shalott (1832/42), but also encapsulated in the painting of the same name (1886-1905) by Hunt. There was an unprecedented revival of the medieval Arthurian legends in the arts and culture of Victorian Britain; its heroes and their romance narratives created metaphors for Victorian notions of monarchy and the roles of men and women in society. Malory’s virtuous Elaine lives passively in the ‘real’ world according to the code of men but she chooses to die ceremoniously in response to her unrequited love for Sir Lancelot.

Tennyson’s and Hunt’s Lady of Shalott is a mysterious adaptation of Elaine. She is afflicted with a supernatural curse and controlled by a mirror which determines her view of the world as she weaves in solitary confinement. When the Lady sees Lancelot though her ‘magic’ mirror her desire for passion and the world results in the abandonment of her art. Here are a few lines for Tennyson’s poem:

Out flew her web and floated wide;

The mirror cracked from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Hunt’s imprisoned Lady is seen at this climactic moment when the curse descends and the mirror cracks conveying an overwhelming impression of exotic sensuality, claustrophobia and the dereliction of duty as an artist. Her entanglement in the tapestry’s broken strands suggests her inner turmoil and the anxieties of Victorian patriarchal society, and yet her aura of coiled energy and explosive mass of hair also anticipate the push for women’s independence in the near future.

As I walked away from the Tate into the heavy fog, the colours and hyper-realism of the art I had just seen stayed with me. This exhibition is an excellent survey of Pre-Raphaelite art and each room could have been a separate exhibition in itself. However, I wonder if visitors would be convinced that this art was avant-garde or just art which looked back to earlier artistic formulae and narratives. Whatever the opinion, I’m sure most will agree that this art evolved as a reaction to the changing face of Britain during a time when the industrial revolution began to bite into the landscape and the workplace, and sexual politics were threatening to expose the double standards of the domestic sphere.

My thanks to Tate Britain for giving me permission to post these images.