The Romans gradually conquered the Greeks during the last two centuries B.C.; it was an epic confrontation—might against culture—but Rome could not remain immune to the beauty and sophistication of Hellenic art. Ancient Greek painting and mosaics have distinguishing features which the Romans borrowed and transformed into their own brand. This artistic ‘hybridisation’ by the Romans was an attempt to emulate Greek artistic heritage and to improve their social and political standing—knowledge of Greek culture was a mark of refinement. Roman tastes in art, literature and philosophy largely determined what survived from ancient Greece.

A major part of Greek art, at least until the Hellenistic period (from 323 B.C. to the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 B.C.), and to a large degree thereafter, evoked images of a rich history. To the ancient Greeks, mythology was their history, and they used their past in a remarkable way to reflect on the present, not only in their literature, but also in their art. The image to the left is a lekythoi (a small closed urn with a narrow ‘mouth’ that was sealed with wax or a stopper, suitable for storing oils, and often used in funeral offerings) owned by the National Gallery of Victoria (©NGV). This Greek ‘vase’ was formed from clay and decorated in the ‘red-figure’ style** by an unknown Greek potter between 440 and 430 B.C. The image features the mythological confrontation of Oedipus and the Sphinx.

A major part of Greek art, at least until the Hellenistic period (from 323 B.C. to the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 B.C.), and to a large degree thereafter, evoked images of a rich history. To the ancient Greeks, mythology was their history, and they used their past in a remarkable way to reflect on the present, not only in their literature, but also in their art. The image to the left is a lekythoi (a small closed urn with a narrow ‘mouth’ that was sealed with wax or a stopper, suitable for storing oils, and often used in funeral offerings) owned by the National Gallery of Victoria (©NGV). This Greek ‘vase’ was formed from clay and decorated in the ‘red-figure’ style** by an unknown Greek potter between 440 and 430 B.C. The image features the mythological confrontation of Oedipus and the Sphinx.

Greek artists who worked for Roman customers under Roman rule painted narratives from Greek mythology as well as pictures based on politics, social order, and real-life scenes: departing warriors, athletes, music and entertainment, slavery, workshops, domestic life, and war. Greek vases not only inspired the Graeco-Roman world in antiquity, but also the western world throughout the centuries. John Keats, the English Romantic poet, thought he grasped life’s meaning by simply gazing at painted Greek vases in the British Museum. His poem, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ (1820), was inspired by the Greek vase:

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! With brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

(Stanza 5)

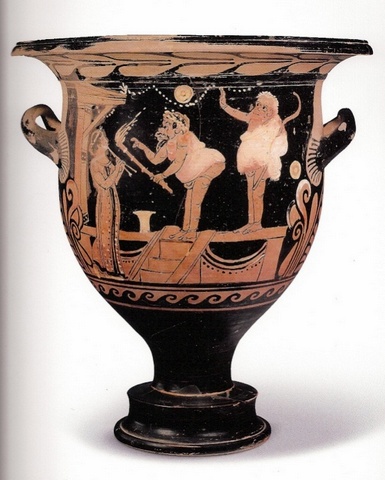

At the end of the fifth century B.C., southern Italian vases were prolific and followed the style and subject matter of Greek vases. The featured image (©NGV) is a decorative bell krater, attributed to the Libation Painter who was principal artist of a group of Campanian vase painters (530 -325 B.C.). A bell krater is ‘red-figure’ pottery in the shape of an inverted bell used for diluting wine with water. The scene is from a a phlyax play featuring two comic actors wearing the Greek New Comedy costume of fitted tights with padding around the stomach and buttocks; both wear masks. New Comedy is Greek drama dating from about 320 B.C. to the mid-third century B.C. that presents a satiric view of contemporary Athenian society, especially in its familiar and domestic aspects, such as thwarted lovers or a cunning slave. The featured bell krater depicts a city slave duping a country bumpkin who is holding a sickle. The city slave is holding a torch and speaking to a musician.

The art of mosaic was a Greek invention of at least the fifth and fourth century B. C., but few survive, and, as the Romans produced many mosaics, especially in domestic settings, it is often assumed that mosaics are a Roman art-form. Mosaic art was continued by the Romans but they used a new technique and more variety in the subject matter. A frivolous subject for a mosaic found in Pompeii around 100 B.C. (image above), and signed by its Greek artist, Dioskourides of Samos, depicts a scene on a stage from a New Comedy which is humorous and animated. It probably copied a second-century B.C. Greek painting, but there could also be consideration of Campanian ‘red-figure’ Greek vases such as the one just mentioned. The mosaicist imitated advanced painting techniques, including shading, highlighting, and multiple colours for this animated scene depicting masked actors playing street musicians on a narrow stage. However, the Greek artist used the new Roman technique of tessellated mosaic, building the scene from pre-cut cubes of stone rather than pebbles used previously by the Greeks.

It’s easy to misinterpret the complexities of this Graeco-Roman cultural interaction if we imagine that Roman engagement with Greek culture was an entirely passive process: that Rome was essentially an empty vessel into which Greek art and culture flowed. In fact, Roman ‘imitation’ of Greek artistic tradition involved creative and ingenious reinterpretation. Greek mythology in painted images was used by the Romans to express moral and political ideas, hopes and aspirations. It can be safely concluded that the art of Rome is the direct heir of Hellenistic art, modified in its new surroundings and embodying strong native elements, yet still a continuous development; an artistic flow or thread which showed respect and indeed, great admiration for the art of ancient Greece.Towards the end of the first century B.C., the Roman poet Horace (65 B.C. -8 B.C.) referred to this cultural exchange:

Captive Greece took captive the savage conqueror and brought the arts into rustic Latium . . .

**Around 530 B.C. the ‘red-figure’ technique was invented whereby the figures were reserved in the red clay and the background black-glazed. Details were painted onto the figures in dilute glaze, which gave the painter greater freedom for drawing anatomy and drapery.

For another time: Pompeii wall paintings

The processes of Roman copying and adaptation of famous images from the repertoire of Greek classics and mythology are clearly documented in the fourth-century wall paintings at Pompeii in Italy, preserved when Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79.

Roman home decor and art collections evoked classical stories, themes and styles, to the extent that Roman culture and Greek traditions fused in opulent villas and houses built in and around the Bay of Naples. The depiction of a dream world prevailed in domestic wall paintings, as if every Roman, depending on his wealth, sought to reproduce the abode of the gods. Landscapes were contrived in accordance with themes borrowed from the repertoire of Greek tradition, and set from time to time in new contexts. Still-life paintings of the foods preferred at Roman aristocratic banquets were combined with mythological scenes which created an authentically Roman style, since the basic ideology and the person commissioning the work were Roman . . .