A warm glow permeates through the latest two-part TarraWarra Museum of Art (TWMA) exhibition, ‘Russell Drysdale: Defining the Modern Australian Landscape’ and ‘Future Memorials’. Many of the museum walls that display Drysdale’s richly coloured paintings and photographs of the Australian outback are a vibrant, yet subdued, gold colour. Sunlight filters through the full-length window at the northern end of the museum space, warming the red bricks in Tom Nicholson’s new installation that resonates with local history. The yellow fluorescent lights of Jonathan Jones’ new work, untitled (muyan), illuminate TWMA’s 45 metre-long Vista Walk Gallery and penetrate into the landscape through the windows (photo below). In this work Jones celebrates the life of William Barak (born c. 1824), the inspirational leader of the local Indigenous Wurundjeri clan during the difficult period of European settlement. The yellow colour and use of light link untitled with Barak’s prediction that he would die when the yellow wattle (muyan) bloomed (he died in August 1903 during wattle blossom) and also to traditional Wurundjeri ceremonies which included two fires, one for the Wurundjeri and one for visitors.

However, although this exhibition celebrates the unique Australian landscape and its cultural history, there is an undercurrent of human loss and disconnection. The landscape paintings of Russell Drysdale (born in England1912, came to Australia 1923, died 1981) depict a harsh, unforgiving Australian interior that not only reflect his despair relating to the negative impact of adverse land management on the environment and the futility of war, but also the fragility of human life. The first group of paintings in the exhibition capture the devastating effects of drought in the Australian interior in the early 1940s which he witnessed as a young man; he also painted the human figure isolated in an alien place or landscape. There are images of sleeping soldiers huddled together for warmth and support on the train station in Albury; by contrast, elongated figures pose in the Australian outback looking more like actors on a stage than real people interacting with the environment. As the exhibition progresses the visitor will note an international modernism and Surrealism creeping into Drysdale’s art, but also his determination to maintain imagery that could be identified as uniquely Australian.

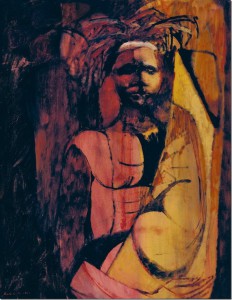

Russell Drysdale, ‘Crucifixion’, 1946, oil on plywood, 76 x 101.6 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, © Estate of Russell Drysdale.

During the mid-1940s Russell Drysdale began to blend symbolism with Australian outback imagery. The bleak apocalyptic landscape painting, Crucifixion (1946), encapsulates the horrors of World War II, including the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima. As curator Christopher Heathcote points out: “there is a macabre twist to the circle of luridly glowing sand that sits on this blasted plain under polluted skies. Here it appears to be, Ground Zero, the target hit by an Atom bomb”. The red and gold barren landscape is surreal: its gnarled trees, drained of colour and life, blend with the decaying organic form of a female standing in the foreground, her depleted body is bent over in a state of deep sorrow as if in prayer.

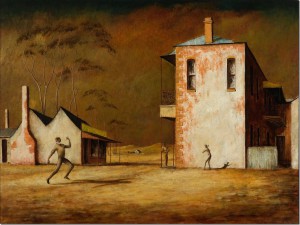

Russell Drysdale, ‘The cricketers’, 1948, oil on composition board, 76.2 x 101.5 cm. Private collection, © Estate of Russell Drysdale.

Midway through the exhibition we see paintings of pensive figures staring wistfully into the empty distance of a barren landscape flat to the horizon (featured image: Evening, c.1945, oil on canvas, 50 x 60.5 cm, private collection, © Estate of Russell Drysdale). Deserted main streets of remote outback towns feature lanky Australians saddling up a horse or playing cricket. As TWMA Director Victoria Lynn suggests, “Drysdale’s works raise many questions to do with how we live in a landscape as harsh as the drought-stricken environment of Australia. They powerfully convey his abiding fascination with the resilience of people and their connection to land.”

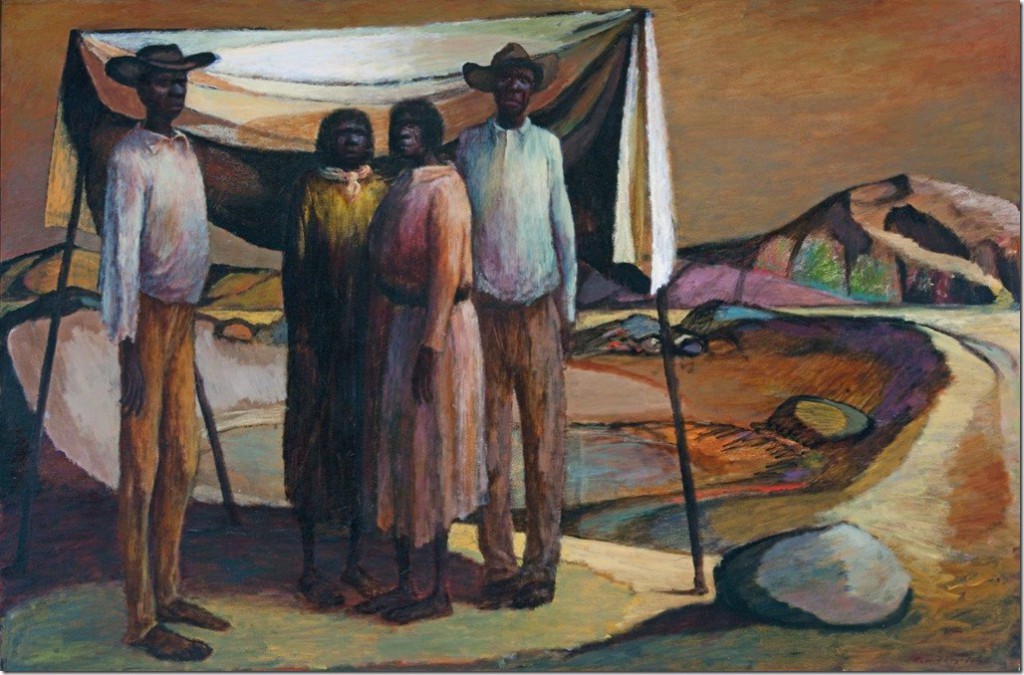

Some of the more affecting images are those of dispossessed Aborigines no longer living according to ancient traditions. Drysdale shows empathy for the plight of these marginalised Indigenous families in paintings such as Mullaloonah Tank (1953), which depicts a group of displaced aboriginals dressed in European clothes and looking directly at the viewer with vacant eyes, alluding to separation from their ancestral country. The white canvas isolates them from the abstracted geological formations in the background yet Drysdale has also linked the four to the land by using the same colours and hues.

Russell Drysdale, ‘Mullaloonah tank’, 1953, oil on canvas, 123 x 183.4 cm. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, © Estate of Russell Drysdale.

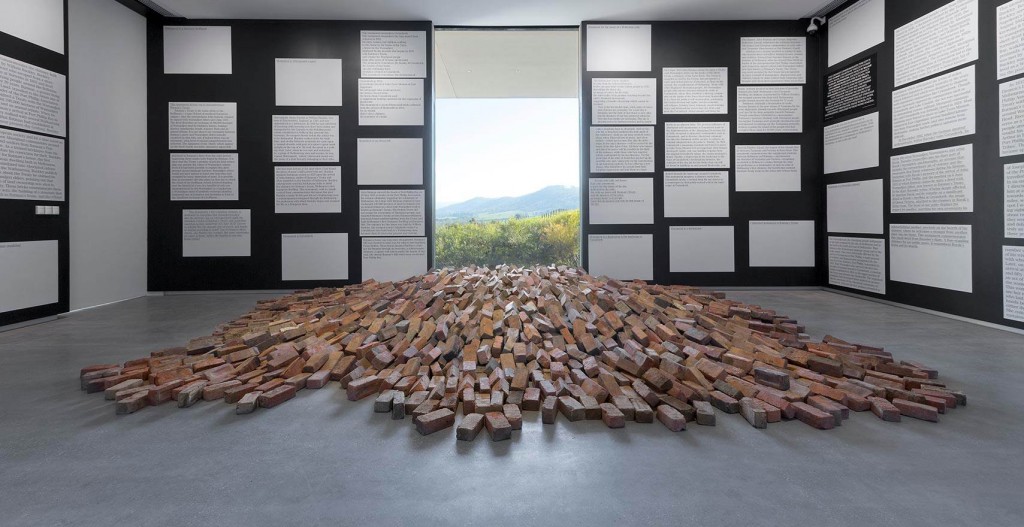

Russell Drysdale’s evocative paintings and photographs of the Aborigines that he encountered in his outback travels provide an opportunity for this TWMA exhibition to link with the past and present of the local Healesville Indigenous community at Coranderrk. In the North gallery, just beyond Drysdale’s paintings, is Tom Nicholson’s new work, Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty (photo below), an installation featuring bricks that have been assembled as if they are being drawn by a magnetic force out of the window and into the spectacular Yarra Valley landscape.

Many of the bricks have been donated by residents from the local community; as such, these bricks are connected with the history of the bricks made in the Coranderrk Station’s kiln, closed in 1924. This ‘monument’ includes the same amount of bricks used in Melbourne’s first chimney built for the European pioneer John Batman, famous for the ‘Batman Treaty’, a land treaty that he ‘negotiated’ with the Wurundjeri (William Barak was apparently present at the signing) in 1835. Nicholson’s installation also includes wall plaques that provide an insight into thoughts regarding the controversial treaty, enabling viewers to ponder its longstanding impact on the original inhabitants of the land.

As mentioned at the beginning of this review, Wiradjuri-Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones’ installation, untitled (muyan), enlivens the Vista Walk Gallery with his tribute to William Barak. Another aspect of this contemporary art project called Future Memorials will involve the collaboration of Nicholson, Jones and Wurundjeri elder, Aunty Joy Wandin Murphy in the creation of a series of 7 site-specific public artworks marking the original boundaries of the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station. Lynn explains that the Future Memorials art project not only signifies TWMA’s commitment to commissioning new contemporary art, but also the museum’s ongoing relationship with the Indigenous history of the local area: “It [Future Memorials] will provide a profound meditation on the nature of the monument as a tradition closely linked to colonialism, and on the possibilities of new kinds of public art making and monuments”.

There is no doubt that Drysdale’s paintings and photographs not only raise questions relating to how humans live in a landscape as harsh as the drought-stricken areas of central Australia, but they also confront the devastating consequences of war and the forced removal of people from their homeland. Both the mid-twentieth-century Drysdale works of art and the contemporary installations of Future Memorials convey hope for the future through lessons learned from the past, which is dependent upon tolerance, vision and the strength of human resilience.

Russell Drysdale, ‘Youth with painted basket, Melville’, c. 1958, oil on canvas, 90.1 x 70 cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection, © Estate of Russell Drysdale.

The exhibition runs until 9 February, 2014.

http://twma.com.au/exhibitions

TarraWarra Museum of Art is Turning Ten!

TWMA opened on December 3, 2003.

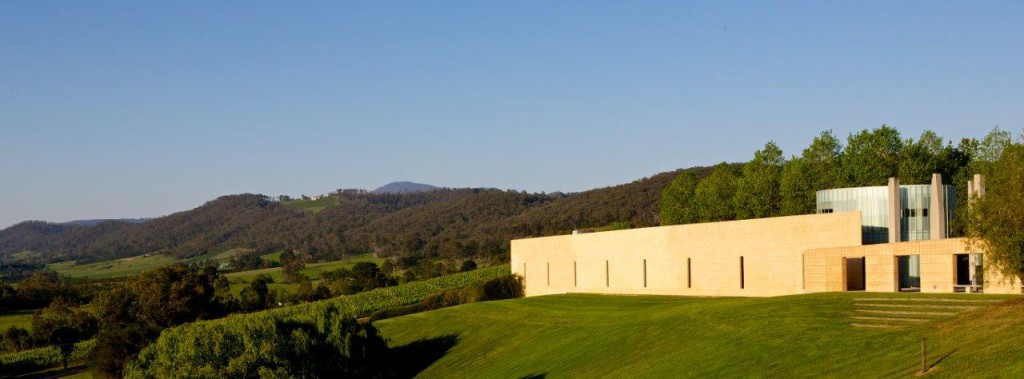

Throughout its first ten years TWMA has featured prominent Australian and international artists in more than 70 separate exhibitions that change with the seasons. A number of the exhibitions have drawn upon works from the TWMA public collection, gifted to the museum by the museum’s founders and patrons Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AO. The Besens have been art collectors since the 1950s and had long dreamed of making a gift of art to the public. The TWMA collection features significant artists who have shaped the development of modern art in Australia and now includes over 500 works by leading figures in Australian modern art. The collection continues to grow each year as key works are added through new acquisitions and donations, further enhancing TWMA’s mission to build an exemplary, enduring collection of modern and contemporary Australian art.

TWMA is the realisation of that gift, bringing together modern art and architecture in a purpose-designed building set in the surrounding natural beauty of the Yarra Valley landscape.

Next weekend (December 7 and 8) the museum will be offering free entry to mark its 10th anniversary. TWMA will also hold a number of free special events and public programmes throughout this special weekend.

Visitors will have the chance to win a prize sponsored by the Healesville Hotel when they participate in the ‘TarraWarra Trail’ to learn about the fascinating Wurundjeri and European history of the museum’s landscape. They may even encounter the living embodiment of the Wurundjeri creator spirit Bunjil when a Wedge-tailed Eagle visits from Healesville Sanctuary, before heading into the museum to view the Indigenous-themed Future Memorials exhibition.

Youngsters can have fun participating in a free ‘Cricket Clinic’ to celebrate Drysdale’s iconic work The Cricketers, currently on display in the exhibition alongside over 35 paintings from major private and public collections. There will also be free live music, delicious casual food and refreshments available for purchase, and a community fund-raising Sausage Sizzle.

TWMA Director Victoria Lynn says, “This beautiful and important museum contributes greatly to the cultural enjoyment of the nation and we look forward to sharing this special celebration of its first decade with all our visitors. We also look forward to launching a new documentary film about TWMA which has been specially made this year.”

A New Collaboration with Healesville Sanctuary:

The visit of a Wedge-tailed Eagle from Healesville Sanctuary also marks the announcement of a new collaboration between the museum and the world famous native wildlife park.

TWMA and Healesville Sanctuary will introduce a special reduced entry fee for visitors who visit both venues during the duration of the Future Memorials exhibition, which runs until the 9th of February 2014. Taking its cue from the proximity of TWMA to the site of Coranderrk Aboriginal Station which was originally located on almost 5,000 acres along the Yarra River between 1863 and 1924, the exhibition explores the effects of colonialism on Wurundjeri people and seeks new ways to understand and renew the relationship between the past and present.

After viewing the Future Memorials exhibition at TWMA, visitors will be able to make a pilgrimage to Healesville Sanctuary to actually ‘step onto Coranderrk’, as the land at Healesville Sanctuary was originally part of the former Coranderrk Aboriginal Mission Station.

Over two Sundays in January next year (Sunday 12 and Sunday 19January), visitors will have a unique opportunity to take a Spirit of the Land Indigenous walking tour at Healesville Sanctuary after learning about the fascinating history of the Coranderrk and Wurundjeri people in a guided tour of the Future Memorials exhibition at TWMA.

Healesville Sanctuary recently unveiled a commemorative life-sized sculpture of William Barak to mark the 110th anniversary of his passing. The bronze sculpture, titled Between Two Worlds, depicts a man caught between two worlds, but able to bridge both, as an ambassador for his people and protector of Wurundjeri traditions and culture. The tour will be led by Wurundjeri Elder Murrundindi, beginning at Barak’s statue then following a natural bushland trail to a Dreaming Place for storytelling where a majestic 250 year old canoe tree proudly stands.

This review does what every review should do: it makes me want to visit, and to visit armed with its insights.

thanks Barrie, this exhibition is very special. I didn’t mention Barak’s carved parrying shield on display . . . an additional delight.