January 1st 2014: time to jab a pin into my list of destinations yet to be explored. Apart from the consideration of important aspects such as available cash and security, travel to distant countries is a lot easier than a century or so ago. Today’s travel writers not only narrate their journeys through the written word but also through images and sound; their subjective eye-witness accounts of intercultural encounters are many and varied, some good, some problematic. Beginning in the late sixteenth century and through to the mid-nineteenth century, British aristocrats, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans, travelled to Paris, Venice, Florence, Naples and Rome to experience first-hand the art and culture of France and Italy. Travel was arduous as most travelled over the Alps in a sedan chair to experience the beauty and sublimity of nature. Itineraries were designed to engender individual improvement and social connections, while returning with cultural ‘souvenirs’ attested to the gaining of taste, distinction and connoisseurship of art ranging from antiquity through to the Baroque. Unravelling the travel narratives of these Grand Tourists within their literary and/or historical contexts, and exploring how these writers juxtapose the familiar with the foreign, is fascinating. The content and literary styles of letters and journals written by exponents of travel during this time, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), John Moore (1729-1802) and Hester Thrale Piozzi (1741-1821) and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), are worth a look.

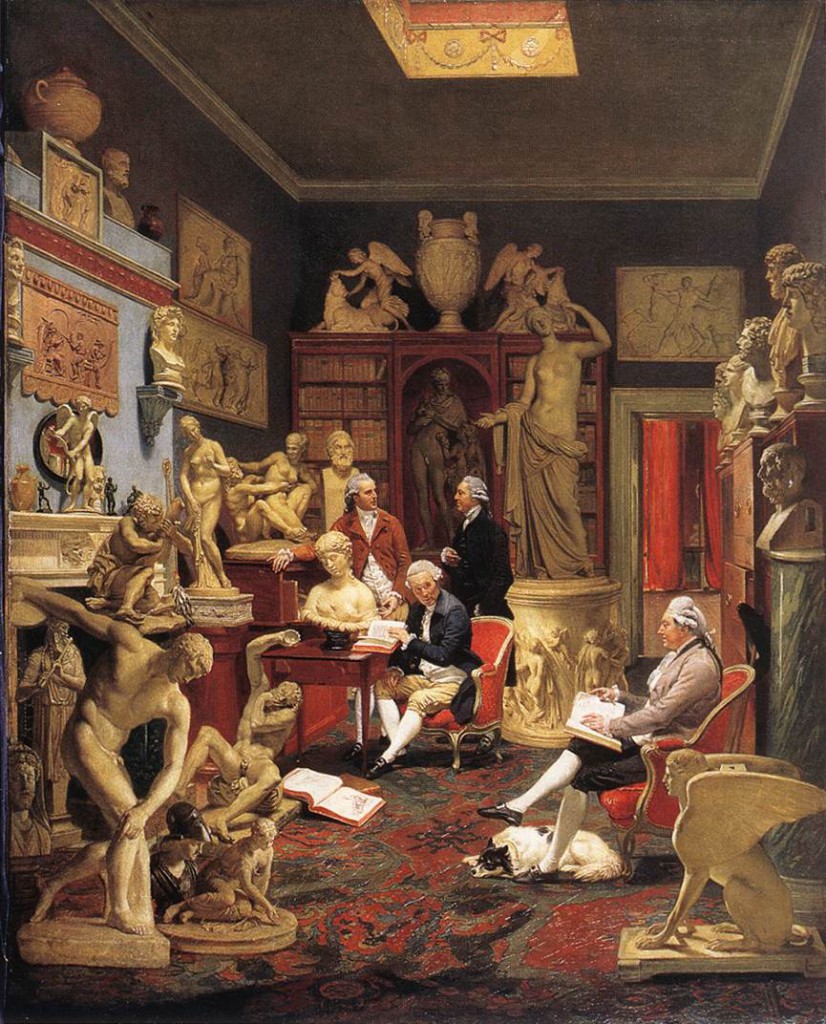

This 1782 painting by Johann Zoffany depicts Grand Tourist, Charles Townley, surrounded by Classical sculptures purchased in Italy (© Townley Hall, Burnley, Lancashire).

In 1781, Scottish physician and writer, John Moore, wrote in his journal, A View of Society and Manners in Italy, about an encounter during his Grand Tour “very early in his life” that occurred when he was viewing paintings at the Palais Royal in Paris; here he observed a gentleman “who had the greatest desire to be thought a connoisseur” and who displayed “all the refinements of his taste”. Moore relates the Paris connoisseur’s hyperbolic response to a painting of St Sebastian: “. . . Pray, gentlemen, observe this St Sebastian, how delightfully he expires: Don’t you all feel the arrow in your hearts? I’m sure I feel it in mine . . . I should die with agony if I looked any longer.” Dr Moore’s satirical view of this man’s “ecstasy of admiration” alludes to his disapproval of overt expressions of passion and emotion when viewing works of art.

Jean Preud’homme, ‘Portrait of Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton’ (on his Grand Tour with Dr John Moore and the latter’s son, John. A view of Geneva is in the distance), 1774, © National Museums of Scotland.

The term, ‘sensibility’, emerged in eighteenth-century Britain and referred to the acute form of responsiveness to aesthetic or physical stimuli. By literally experiencing the world physically, the Grand Tourist’s sensibility became an emotional display that linked to the philosophy of empiricism (that all knowledge is based on the senses). Swiss philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), promoted this new form of responsiveness, which he believed, apart from extreme feelings of passion, was important for morality and in exchanges between people. Mary Wollstonecraft, in her book, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), abhorred women turning into “creatures of sensation”, which she believed encouraged them to develop an “overstretched sensibility”.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, British women took more of an active role on the Grand Tour. Women travelling to the Continent included English literary figure, Hester Thrale Piozzi, who, in 1789, lived in the small Italian community of Lucca (between Pisa and Florence) with her Italian husband, Gabriel Piozzi. Hester Piozzi’s acclaimed journal, Observations and Reflections made in the Course of a Journey through France, Italy, and Germany, often mocked the British. In London, Hester Thrale was embraced by the upper middle class literary ‘blue-stocking circle’ of women (‘blue-stocking’ refers to the dress of the men who were included in the celebrated salon, such as Samuel Johnson) who engaged in rational conversation and encouraged individual opinion. However, social exclusivity and snobbishness were inherent in her circles, and when she flouted convention by marrying an Italian Roman Catholic (her first husband was the wealthy English brewer, Henry Thrale), at the age of forty-three, she was excluded.

Joshua Reynolds, ‘Mrs Hester Lynch Thrale with her Daughter Hester Maria’, 1777-8,

© Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

Mrs Thrale, soon to be Hester Piozzi, was renowned for her sharp tongue and caustic wit; she disliked the portrait by Reynolds and told a friend that “there is really no resemblance, and the character is less like my father’s daughter than Pharaoh’s”. She wrote:

In Features so PLACID, so Smooth, so Serene,

What trace of the Wit – or the Welch -WOMAN’S seen?

It is understandable that Hester sought a considerable degree of emotional as well as intellectual freedom that had been denied to her by the constraints of home. Piozzi referred to Lucca, which was passed over in most Grand Tour itineraries, as “this fairy commonwealth”, where “liberty is written up on every wall and door”. Her informal and eccentric style of writing enhances the foreign content, such as when she describes the colourful mode of dressing for church at Lucca: “the church at noon looked like a flower-garden, so gaily adorned were the priests….” Here she emphasises difference from home, supporting her acceptance of variety.

Hester Piozzi’s narratives of enthralment as she witnessed Italian art and sublime landscapes qualify her heightened sensibilities, branded as vulgar by those ‘back home’. In 1784, Hester Piozzi exclaimed as she traversed the Alps that, “every step gives a new impression to the mind . . . while the portion of terror excited either by real or fancied dangers in the way, is just sufficient to mingle with pleasure . . .” Confrontations with the ruggedness of the scenery engendered “terror” in the face of the destabilising power of nature, and as Piozzi concludes “… makes one feel the full effect of sublimity”. The new association with the dramatic and primitive features of more wild terrain owed much to the writings of Edmund Burke’s Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Beautiful and the Sublime (1756). Burke’s thesis was that all emotion is sensation and has a physical basis, and that all physical phenomena are divisible into the sublime and the beautiful according to the emotional response elicited.

Joseph Wright of Derby, ‘Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples’, c.1776-80, © Tate Britain, London.

Piozzi describes the awe-inspiring view of Mt Vesuvius: “One need not stir out for wonders sure, while this amazing mountain continues to exhibit such various scenes of sublimity and beauty”. On viewing Herculaneum and Pompeii, Hester Thrale Piozzi borders on the hyperbolic when she writes: “How dreadful are the thoughts which such a sight suggests! How very horrible the certainty, that such a scene may be all acted over again to-morrow; . . .” These hyperboles of indescribability affirm the Grand Tourist’s eye-witness status as having encountered foreign landscape and cultural objects in person. Piozzi also exhibits spontaneous responses to art and disdains those connoisseurs who coldly analyse paintings such as Bassano’s The Raising of Lazarus (1573-1622, Galleria dell’ Accademia, Venice): “. . . Lazarus . . . reawakened suddenly to a thousand sensations at once, wonder, gratitude, and affectionate delight! . . . How can one coldly sit to hear the connoisseurs admire the folds of the drapery?” (1789)

A final word from Hester Thrale Piozzi:

Il mondo e bello perche e variabile: “The world is pleasant because it is various”

The featured image is a photo I took in the Vatican Museum of the marble sculpture, ‘Silenus with the child Dionysus (Bacchus)’, on 8 January 2009. The Roman statue is a copy of the Greek original from the school of Lysippus, 2nd century AD, (original 4th c. BC), (Museo Chiaramonti, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City). This sensitive portrayal of nurturing would have appealed to the sensibilities of the enlightened Grand Tourist.

References

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm

Elizabeth Bohls and Duncan Ian, (editors), Travel Writing 1700-1830, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Chloe Chard, Pleasure and Guilt on the Grand Tour: Travel Writing and Imaginative Geography, 1600-1830, Manchester: Manchester UP, 1999.

Brian Dolan, Ladies of the Grand Tour, London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2001.

Happy New Year to all! I’ll be back with new articles from February 1st, although I’ll be tweeting on and off . . .

First rate, again, Denise. I enjoyed it very much.

Do you know the letters of Johnson to Hester Thrale’s daughter, whom he called ‘Queenie’? He delighted in her, and gave her a ‘cabinet’ to keep her curios in.

The letters are in a collection edited by The Marquis of Lansdowne called The Queenie letters – letters to her from her mother, Fanny Burnie and SJ.

Apologies for the late response, Barrie – have you heard of computer glitches? Appreciate passing on your knowledge of Samuel Johnson and his connection with the Bluestocking Circle of ‘enlightened’18th-century British women.