Traditionally, the first day of January challenges us to take a critical look at ourselves and reflect upon who we are, or who we’d like to be. Our sense of identity is important to us. Have you ever looked at yourself in the mirror, like I have, and thought about drawing, or even painting a self-portrait? How would you depict yourself? Indulging in your interests, or holding your tools of trade? Would you widen the perimeter of the mirror and surround yourself with your family and friends, or place yourself within your society? You may prefer to be in disguise? Exposing oneself on Facebook or taking a smartphone selfie has little to do with a truthful self-representation. But do self-portraits need to have anything to do with the truth? For artists, self-portraits reveal something far deeper than their own physical looks—they are more interested in conveying an idea of how they wish to be viewed by the world, and by themselves.

Are we to paint what’s on the face, what’s inside the face, or what’s behind it? Pablo Picasso

The genre of self-portraiture became popular in Europe during the fifteenth century when the artist was revered as divine, or a genius, removed from manual work. In 1500 Albrecht Durer reflected this idea when he painted his self-portrait as the image of Christ and ideal male beauty—he also allowed the viewer access to his interior self through his piercing direct gaze.

Artists advertised their talents by including themselves in the action of paintings, altarpieces and frescoes. Sometimes the artist is easily recognised in the group of figures; in other instances, an artist’s presence can be guessed when one of the figures draws attention to himself by the fixity of his stare towards the viewer. Sandro Botticelli’s The Adoration of the Magi (c. 1475) was commissioned by Gaspare del Lama, who insisted that the Magi were painted in the likeness of members of the powerful Medici family. Del Lama is portrayed as the old man on the right with white hair and a light blue robe. It is alleged that the blond man with yellow mantle on the far right looking directly at the viewer is the artist himself. The presence becomes, in a sense, the signature. What scene or narrative would you paint yourself into?

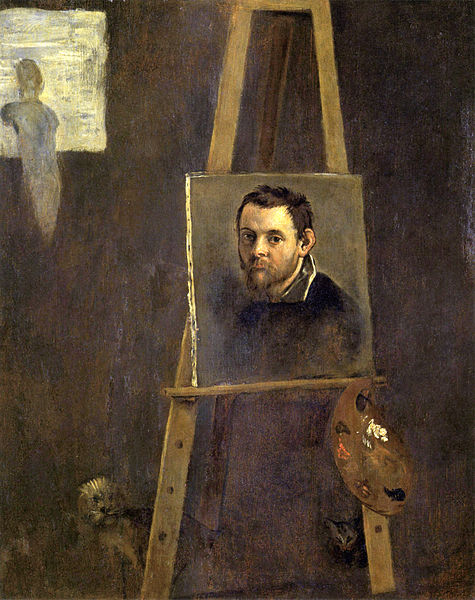

Annibale Carracci, ‘Self-portrait on an easel in a Workshop’, c. 1605, oil on wood, 370 x 320mm, Uffizi, Florence

In 1605 Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) painted his melancholic image—which links with sixteenth-century tradition of the artist as a melancholic type—in Self-portrait on an easel in a Workshop, exemplifying the metaphor of the mirror as self-scrutiny; however, here the mirror is the canvas placed on a simple easel in contemplation of the finished work. This humble self-portrait not only reflects Carracci’s simple beginnings as a tailor’s son, but transcends the presentation of the artist as a genius who shuns manual work. To Michelangelo’s claim that “we paint with our brain, not with our hands”, Carracci apparently responded, “we painters have to speak with our hands”. The dark image depicts Carracci as an unkempt, solitary figure in working clothes, his palette and brushes acting as a personal signature. The artist has removed himself from the painting and his studio, joining the viewer to contemplate the nature of his art after the creative process has finished. The visual result is striking: light falls across Carracci’s face as he gazes directly at the viewer in a pensive yet intense way; his dog reflects Carracci’s expression. Where would your ‘mirror’ be located?

In 1656 the Spanish artist Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) painted himself in one of the most famous, and enigmatic, of all representations of the artist at work: Las Meninas. Here he is standing informally amongst the Spanish royal family, parading his position as the court painter to Philip IV of Spain. The “meninas” are identically-dressed maids who fuss over the Infanta Margaret Theresa, a fashionably-dressed girl who stands before her royal parents while Velazquez paints them (they are reflected in the mirror at the back of the room). Velazquez projects ambition and pride with Baroque flair as he pauses from his work holding his palette and brushes, as if he is inviting the viewer to consider the painter as worthy of nobility. The self-portrait plays with the idea of reality (through the inclusion of mirrors and open doors) and identity.

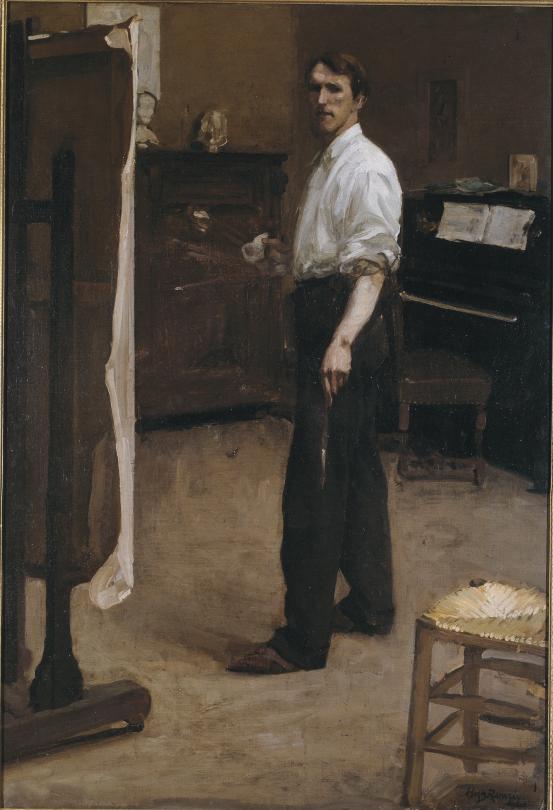

Hugh Ramsay, ‘Portrait of the artist standing before easel’, 1901-2, oil on canvas, 131 x 90 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

In his self-portrait, Portrait of the artist standing before easel, Australian artist Hugh Ramsay (1877–1906) has depicted himself in his shared Paris studio in the act of painting; and in doing so he pays homage to one of his artist-heroes, Diego Velasquez. The work is obviously influenced by Les Meninas, not only in the tone of the painting and Ramsay’s stance before the easel, palette and brush in hand, but in capturing the moment when the artist pauses from his work, as if he is addressing the viewer about what it means to be a painter. Ramsay’s proud demeanour conveys a commitment to his vocation at the age of 24. Unfortunately he died five years later of tuberculosis.

Artemisia Gentileschi, ‘Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting’, 1638-9, oil on canvas, 965 x 737 mm, Queen Elizabeth II Royal Collection

Artemisia Gentileschi’s self portrait of 1638-39 provides a bird’s-eye view of her artistic creativity embodied in an abstract allegory, which was literally unavailable to male artists. She presents herself as ‘Pittura’, the female representation of Painting, described in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, a dictionary published in Rome in 1593. In this self-portrait she has chosen to identify directly with Painting, subverting contemporary ideas of a masculine intellect being superior to the passivity of the feminine. Dressed like ‘Pittura’ in a lustrous garment with gold chain and pendant mask representing imitation, Artemisia has the same dishevelled hair, which is associated with intellectual frenzy, and they both clasp brushes and palette, the tools of an active painter. The brush in the artist’s right hand is moving forward with her powerful arm raised towards a canvas; but her chest and face are in the light, emphasising her feminine creativity. Artemisia’s embodiment of ‘Pittura’ as she engages in her profession is regarded as her insistence that the worth of the art of painting does not derive from association with royalty, which Velazquez sought, but from simply doing her work. Born in Rome in 1593, she was taught by her father, the acclaimed painter, Orazio Gentileschi. When she was nineteen, Artemisia famously accused an associate of Orazio’s, Agostino Tassi, of rape and took him to court. Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting is an example of a self-portrait that projects the artist’s sense of identity and individual perception of his or her connection with art.

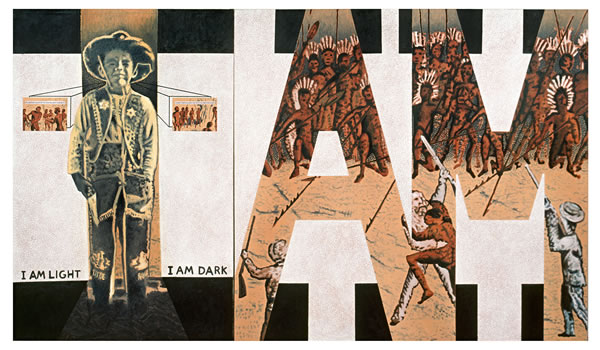

Aboriginal artist Gordon Bennett (1955-2014) was aware of how the sense of self can be a construction by others. For him, self-portraits not only acknowledge his confused childhood spent as an Aborigine living in a ‘white’ European society (his father was ‘white’), but also explore the broader issues of identity for Indigenous Australians, which include the effects of cultural inequalities created during European settlement in Australia.

Gordon Bennett, ‘Self-portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys)’, 1990, oil on canvas, 150 x 260 cm, private collection, Brisbane

In Self-portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys) Gordon Bennett questions how stereotypes create an unhealthy sense of identity.

The powerful image/word ‘I AM’, while central, is accompanied by statements of opposite, ‘I am light – I am dark’. Bennett’s portrait of himself as a four-year old boy dressed as a cowboy as the ‘I’ is juxtaposed with images of Aborigines as the ‘AM’. Clear visual divisions are created with distinct black areas as well as large white areas. The title of the work itself is unsettling. It exposes the pain these stereotypes create. Bennett attempts to destroy the stereotypes to question notions of identity. (NGV Education resource)

Bennett died in June 2014 and Kitty Hauser (The Australian, August 2014) wrote of him:

Bennett, who died in June, never allowed his work to be exhibited as Aboriginal art. He did not see himself as an Aboriginal artist, not just because it was a label (by definition) imposed by a dominant culture but also because it whitewashed the Anglo-Celtic half of his heritage. He did not negatively judge his racist father. He was interested in how both sides effectively suffered from the violence and from the silence about it; he made images that interrogated the nation’s self-image so that it would be hard to see things in the same way again.

At the heart of human life is a complex concept of the self. The painted or sculpted self-portrait is never just a recreation of the physical appearance of the creator; it attempts to convey the essence, and often the beliefs, of the individual. However, some artists use self-portraits to mask their identities, or even project themselves and their experiences of life through another image . . . I’ll leave that for a future article:

Self-Portraits 2: The Masked Face

In the meantime you may like to read a new book on self-portraiture:

James Hall, art historian and critic, thematically examines an extensive range of self-portraits, from the Middle Ages to Durer, Rembrandt, Velazquez, through to the present day. Hall’s writing style is scholarly without being condescending, and the book, published by Thames & Hudson in 2014, is a quality production.

***

Featured painting: Joshua Reynolds, ‘Self-portrait’, 1747-49, oil on canvas, 635 x 743 mm, National Portrait Gallery, London

Denise, thank you for a wonderful article and exploration of such different and intriguing works. I don’t have a favourite, but love them all, each in their own right. And you have analysed them with much insight and opened my eyes to the self portrait and why an artist paints them.

I, for my part, paint them for lack of a sitter!

Thankyou. I always enjoy your articles.

Nita J.

Thank you for your kind words, Nita. I look forward to seeing your self-portraits.