‘Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.’ Virginia Woolf’s famous essay ‘A room of one’s own’ (published 90 years ago, in 1929) is a rallying cry for women’s intellectual and social freedom – a feminist tract that calls attention to the missing voices of women from the literary record across centuries, silenced by virtue of their perceived inferiority. Woolf demanded space for women in intellectual discourse, challenging the male-dominated institutions of learning to open their doors to all people equally.

The State Library of Victoria has a proud (and unusual) history of equality of access for all (aged over 14, at least!): it is one library that will never be locked up. In our free World of the book exhibition this year, a special display focuses on the history of the struggle for women’s equality – intellectual, political, and physical – in the English-speaking world, from the 17th century to the present day. Over the course of three blogs, we’ll explore this display.

Education for all

It could be argued that the basis for social and political equality is educational equality, and this has been a running theme in the ongoing quest for women’s rights around the world: education is empowering. From the ancient world to the early modern period, few European women had access to the education regularly provided to men from middle and upper-class families: those who did were extremely wealthy and/or sequestered in nunneries.

In a European context, one of the earliest and most significant voices in this regard – and an example of the role of wealth in women’s enfranchisement – is Christine de Pizan, (1364–c1430), a Venetian-born member of the French court of Charles V, where her father Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano was court astrologer. Christine received an excellent education at the court, and occupied a privileged place, exposed to the leading thinkers and artists of her day. She married a royal secretary, Etienne du Castel, in 1379 (when she was 15) and had three children before his death in 1389 from the plague.

Christine de Pizan writing, from British Library, Harley MS 4431, c1410–14 (not part of the World of the book display).

Christine turned to writing professionally as a source of income when she was widowed. She went on to produce an influential body of vernacular and Latin poetry and prose, from love ballads to political treatises. ‘The book of the city of ladies’ was completed around 1405 and describes a symbolic city solely occupied and governed by women. (You can view a digitised version of one of the surviving manuscript copies of the text held by the British Library.) Through the allegorical female figures of Reason, Justice and Rectitude, Christine argued for women’s moral, intellectual and theological equality with men. She pointed out that negative stereotypes of women were allowed to flourish because women were excluded from public intellectual life: if women are given voices, she opines, their true significance and worth will be self-evident.

This text was widely read in Christine’s lifetime and was in circulation well into the 16th century, along with her other writings. After a period in the shadows, her work was embraced and highlighted by 20th-century historians and philosophers (including Simone de Beauvoir, author of Le deuxieme sexe, which will be discussed in part three of this blog series) keen to listen to the voices of women of the past.

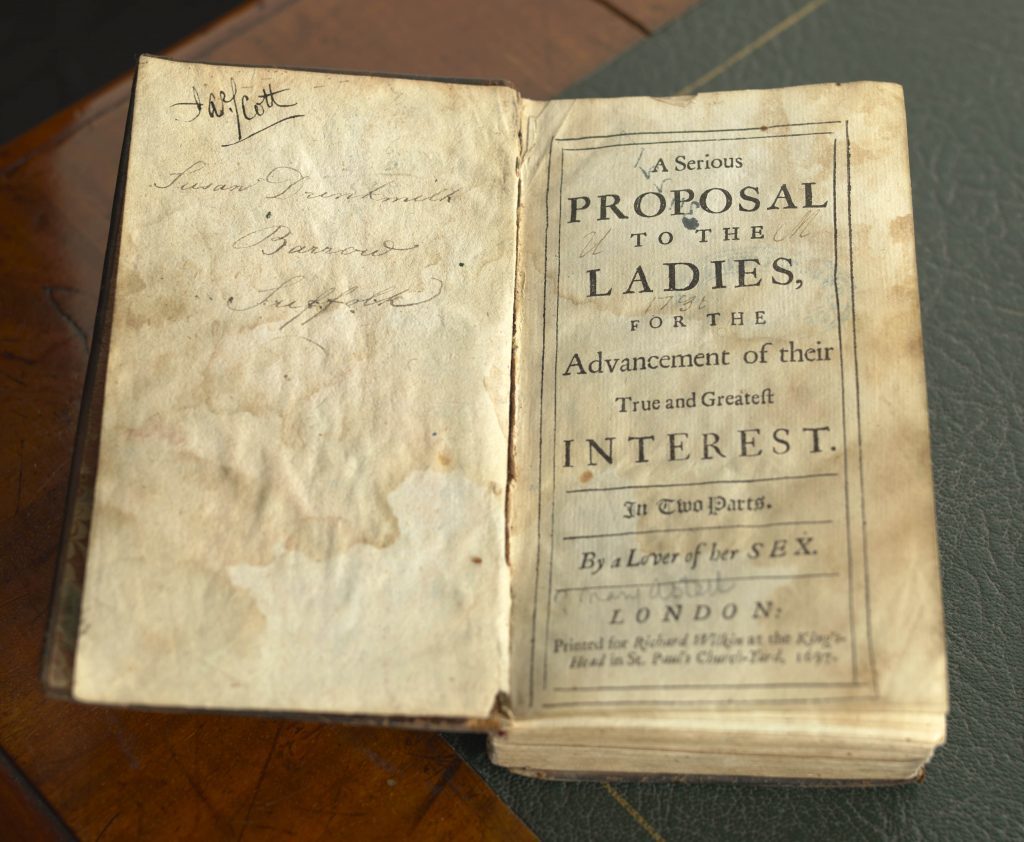

Christine’s influence on a key thinker in the feminist canon, Mary Astell (1666–1731), is clear. In her book ‘A serious proposal to the ladies, for the advancement of their true and greatest interest: in two parts: by a lover of her sex’, (first published 1694), the radical English philosopher and feminist Astell proposed a new system of female education that facilitated both religious and secular learning for all women, offering them career opportunities beyond those of nun or mother. Astell’s own education had been limited: she received only informal education (though was fortunate that it included some exposure to ancient philosophy) from an alcoholic ex-clergyman uncle. The misfortune of being left without a dowry, and thus unlikely to be married, became an advantage: she moved to Chelsea with an aunt, where she became part of circle of wealthy literary women who encouraged her writing and publication.

Mary Astell, ‘A serious proposal to the ladies, for the advancement of their true and greatest interest: in two parts: by a lover of her sex’, London, 1697 edition.

Astell’s focus in women’s education was part of her broader intellectual project to establish the rationality of women, countering the characterisation of the feminine as an essentially irrational force, and the female as a biologically inferior version of the male (an idea with long, much-analysed roots in ancient philosophy). Though never adopted, her system stirred the desire for equality in women of her generation and beyond, inspiring Mary Wollstonecraft and others in their quest for women’s political enfranchisement.

One famous literary descendent of Astell is Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) whose essay ‘A room of one’s own’ has already been mentioned. Much had changed between Astell’s life and Woolf’s, and yet formal education for girls and women was still not the norm. First published in 1929, Woolf’s essay drew on lectures she delivered at Newnham and Girton, two women’s colleges at the University of Cambridge. Her topic was ‘women and fiction’, which led to reflections on the conditions necessary to produce fiction, which include economic independence: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” The phrase ‘a room of one’s own’ has become part of our common cultural vocabulary today.

George Beresford, Virginia Woolf, July 1902 (aged 20), platinum print, National Portrait Gallery, London

Though well educated at home by liberal, highly literate parents, Woolf did not attend university, unlike her brothers Thoby and Adrian. With characteristic sharp wit and erudition, in this essay she lays bare the difference in the opportunities available to men and women, and the structural impossibility of equality between the sexes without equality of education and economic power. Famously, she muses on the lost voice of Judith, Shakespeare’s (fictional) gifted sister, who is denied the education her brother receives:

She was as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world as he was. But she was not sent to school. She had no chance of learning grammar and logic, let alone of reading Horace and Virgil. She picked up a book now and then, one of her brother’s perhaps, and read a few pages. But then her parents came in and told her to mend the stockings or mind the stew and not moon about with books and papers. They would have spoken sharply but kindly, for they were substantial people who knew the conditions of life for a woman and loved their daughter—indeed, more likely than not she was the apple of her father’s eye. Perhaps she scribbled some pages up in an apple loft on the sly but was careful to hide them or set fire to them. Soon, however, before she was out of her teens, she was to be betrothed to the son of a neighbouring woolstapler. She cried out that marriage was hateful to her, and for that she was severely beaten by her father. Then he ceased to scold her. He begged her instead not to hurt him, not to shame him in this matter of her marriage. He would give her a chain of beads or a fine petticoat, he said; and there were tears in his eyes. How could she disobey him? How could she break his heart? The force of her own gift alone drove her to it. She made up a small parcel of her belongings, let herself down by a rope one summer’s night and took the road to London. She was not seventeen. The birds that sang in the hedge were not more musical than she was. She had the quickest fancy, a gift like her brother’s, for the tune of words. Like him, she had a taste for the theatre. She stood at the stage door; she wanted to act, she said. Men laughed in her face. The manager—a fat, loose-lipped man—guffawed. He bellowed something about poodles dancing and women acting—no woman, he said, could possibly be an actress. He hinted—you can imagine what. She could get no training in her craft. Could she even seek her dinner in a tavern or roam the streets at midnight? Yet her genius was for fiction and lusted to feed abundantly upon the lives of men and women and the study of their ways. At last—for she was very young, oddly like Shakespeare the poet in her face, with the same grey eyes and rounded brows—at last Nick Greene the actor-manager took pity on her; she found herself with child by that gentleman and so—who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body?—killed herself one winter’s night and lies buried at some cross-roads where the omnibuses now stop outside the Elephant and Castle.

That, more or less, is how the story would run, I think, if a woman in Shakespeare’s day had had Shakespeare’s genius.

This thought experiment continues to inspire critique and debate today, 90 years since its publication. The recovery of absent voices from the historical record is now a standard area of inquiry for historians of all periods and for contemporary cultural commentators, and not only regarding women: the focus on the voices of people of colour, those with disabilities, and the LGTIBQ+ communities is an important development. One feels Woolf would be pleased to know about initiatives such as Project continua, which digitally archives women’s intellectual history “to enable widespread access to this critical mass of data.” Women’s voices are being heard more clearly today than ever before in recorded history. However, there’s still work to do! Both Christine de Pizan and Virginia Woolf are represented in this display by the editions of their works included in the Penguin ‘Great ideas’ series; only six of the 100 books in this series are by women, and two of these are by the same author (Woolf).

Read part two of this series of posts: Political Equality

I am delighted that Anna Welch, book historian (specialising in medieval history) and curator at the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne has agreed for me to post this article that she wrote for the SLV’s blog on 4 March.