Silence is a tool that writers of fiction can use to great effect. By silencing a character in a poignant moment, emotion is heightened; interrupting action with silence can magnify drama; allowing a character to inhabit a space devoid of action allows time-out and an opportunity for reflection. For examples of silences in literary writing, seek out authors such as Kazuo Ishiguro who emphasise silence as a means of establishing character, and atmosphere over plot and action.

In Ishiguro’s mesmerising The Remains of the Day (1989), the ageing butler, Stevens, ‘shows’ the reader his regrets much more precisely through the things that he fails to tell. What is left unsaid paints the reality: his disillusionment, his losses, and his lonely existence that consciously rejected companionship and love.

A painting can convey silence in a similarly haunting way to invite a response from the viewer. In Ford Madox Brown’s 1855 painting (above), ‘The last of England’, there is chaotic action in the background, and the wind is fierce, but the vision of the silenced couple in the foreground, with their fixed gazes, conveys a profound sense of tension.

The essence of a character in fiction does not have to be drawn out in dialogue or in lengthy descriptive passages; sometimes silences tell (show) the reader more about a character. Silences are a means of providing spaces in the narrative for readers to reflect on what has just happened.

In The God of Small things (1997), author Arundhati Roy allows room for readers to soak up the atmosphere and tension of pivotal moments in the narrative through staccato pauses or long silences. For example:

The Inspector asked his question. Estha’s mouth said Yes.

Childhood tiptoed out.

Silence slid in like a bolt.

Someone switched off the light and Velutha disappeared.

The short sentences reveal so much in just a few words. Then there is white space so the reader has time to ponder the revelation and its possible implications. Not only is there silence, but the light is switched off.

Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park (1814) is full of silences and absences. Fanny Price, the ‘quiet auditor of the whole’, gains moral strength through silent observation. Fanny’s silences move from silences that are created through her abject misery of resignation, to a life as the poor relation, to silences that are a means of gaining an acute perception of self and the world around her. When Mary Crawford articulates her brother’s self-serving love for Fanny the narrator tells us: ‘Fanny could not avoid a faint smile but had nothing to say’.

In Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), Bernard longs for silence and solitude:

‘How much better is silence; the coffee-cup, the table. How much better to sit by myself like the solitary sea-bird that opens its wings on a stake. Let me sit here for ever with bare things, this coffee-cup, this knife, this fork, things in themselves, myself being myself.’

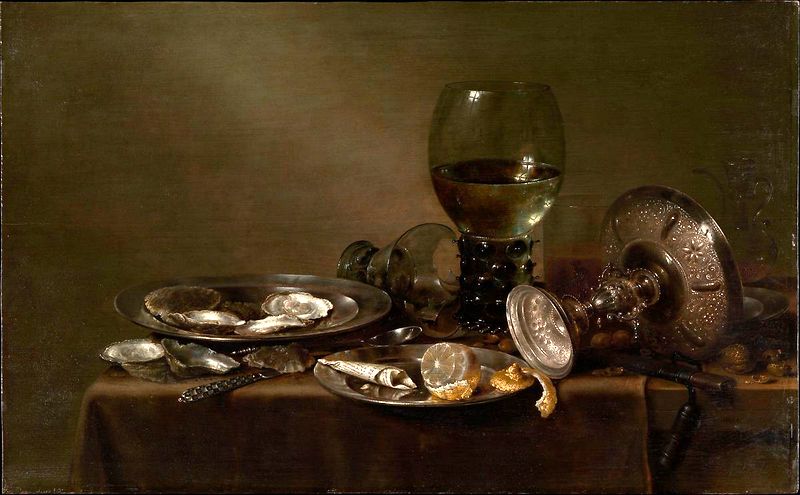

Willem Claesz Heda, ‘Still Life with Oysters, a Silver Tazza, and Glassware’,1635, The Met, New York

This brings to mind still-life paintings with half-empty glasses, used utensils and leftover food that evoke the silent aftermath of a robust encounter; the viewer can only imagine what might have been said, or left unsaid, by the humans, now departed. I recall the surreal experience of walking silently through Dennis Severs’ East London house that has been transformed into an eighteenth-century museum-home where the inanimate objects have been arranged to look like the inhabitants have just left the room—there is a silent confusion between still-life and the evocation of a moving ‘landscape’. I felt like a protagonist walking in a labyrinth inhabited by ghosts. Writers of fiction can create a similar atmosphere and related drama by incorporating scenes of silent evocations of a living space after the human noise has been removed.

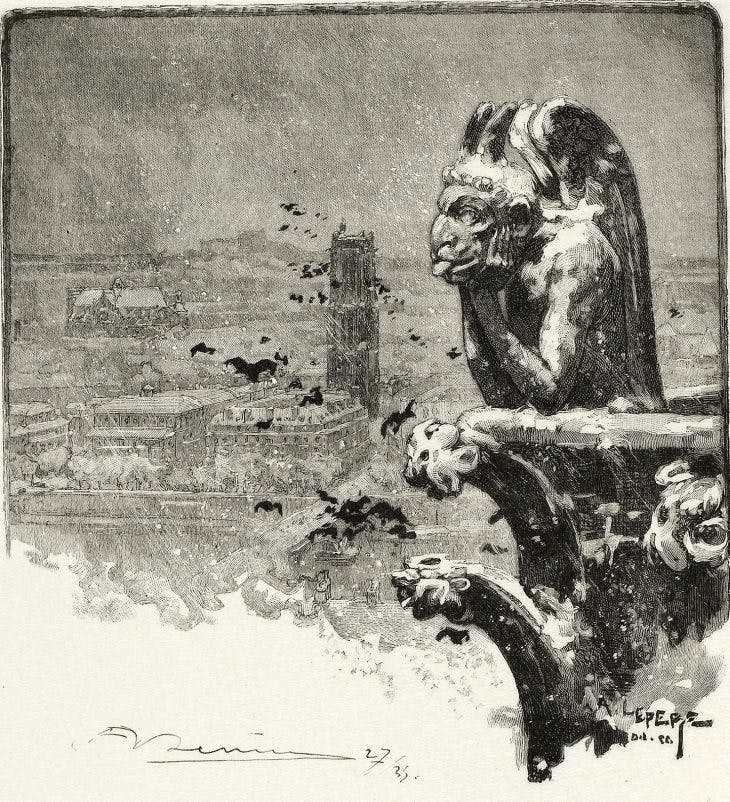

On 15 April this year a fire broke out in the gothic Paris cathedral, Notre-Dame, which drew me back to the times when I stood in cavernous cathedrals and churches throughout Europe, enjoying the peace and slower pace of human activity. I recall Lambert Strether, the main character in Henry James’ The Ambassadors (1903), sitting in the solitude of Notre-Dame de Paris.

It wasn’t the first time Strether had sat alone in the great dim church – still less was it the first of his giving himself up, so far as conditions permitted, to its beneficent action on his nerves. [. . .] He trod the long dim nave, sat in the splendid choir, paused before the cluttered chapels of the east end, and the mighty monument laid upon him its spell. [. . .] Justice was outside, in the hard light, and injustice too; but one was as absent as the other from the air of the long aisles and the brightness of the many altars.

‘The Vampire of Notre-Dame’, plate nine from Le Long de la Seine et des Boulevards (1890/1910), Louis Auguste Lepère, published by A. Desmoulins. Art Institute of Chicago

We live in a society that exalts the extrovert. Action and words are often valued more than quiet, private contemplation. Some of the most powerful scenes in narratives are when characters remain silent, or inhabit spaces that remove them from the noise. Silences in pivotal moments not only allow a character time for reflection, but also encourage the reader’s imagination—not everything can be, or needs to be, known. Sometimes what is left unsaid exerts the most compelling power.

Manuscript Assessments

If you would like an assessment of your unpublished novel, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then please refer to my Manuscript Assessments page for my fee schedule. If you would like to ask me a few questions about this assessment service then I would welcome your email via my contact page.

If you would like an assessment of your unpublished novel, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then please refer to my Manuscript Assessments page for my fee schedule. If you would like to ask me a few questions about this assessment service then I would welcome your email via my contact page.

A manuscript appraisal looks at the big picture and does not correct mistakes or make comments directly on the manuscript; this service is provided in the editing or proofreading process.

Featured image: Ford Madox Brown, ‘The last of England’, 1855, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Reference: Laurence, Patricia. “Women’s Silence as a Ritual of Truth: A Study of Literary Expressions.” Austen, Bronte and Woolf in Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. Eds. Elaine Hedges and Shelley Fisher Fishkin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.