We’ve all deleted or manipulated photos of ourselves if we don’t like the way we look. So do we really care if our ‘self-portraits’ are just constructions, images of ourselves that we want to convey, at a particular place and moment in time? Self-portraits that mask the identity of the artist are often slammed as being pretentious and gimmicky, disallowing any intimacy with the viewer; but some of the masking is another way of projecting or exposing the self, and the artist’s fears and aspirations, beliefs and frustrations. I’ve chosen five self-portraits that scratch the surface of the oblique self-portrait.

Cindy Sherman, ‘Untitled’ from the ‘History portraits’ series 1988-90, 1988, printed 2003, type-C photograph, 94.2 x 57.5 cm, NGV, Melbourne.

Let’s begin in the United States during the 1980s, a time when individuals were reinventing themselves and living transitory lives. In her History portraits series 1988-90, as in her earlier black-and-white film stills works, we see photographer-artist Cindy Sherman (born 1954 in New Jersey) posing in multiple guises, suggesting the constructed nature of identity. In Untitled (1988) Sherman’s self-portrait gives little away: caked-on make-up, plastic bustier and low-cut lacy gown. This powdered ‘self’ plays with notions of old master paintings of the eighteenth century, gender roles, body image, and feminine beauty. Her icy stare and pouty red lips pierce through the cool greenish tint of the photograph, but the viewer is not allowed any access to the ‘true’ identity of this buxom sitter. Sherman is juxtaposing the supposed realism of photography with the obvious staged scene, which includes herself as the performative self. This self-portrait is pure masquerade.

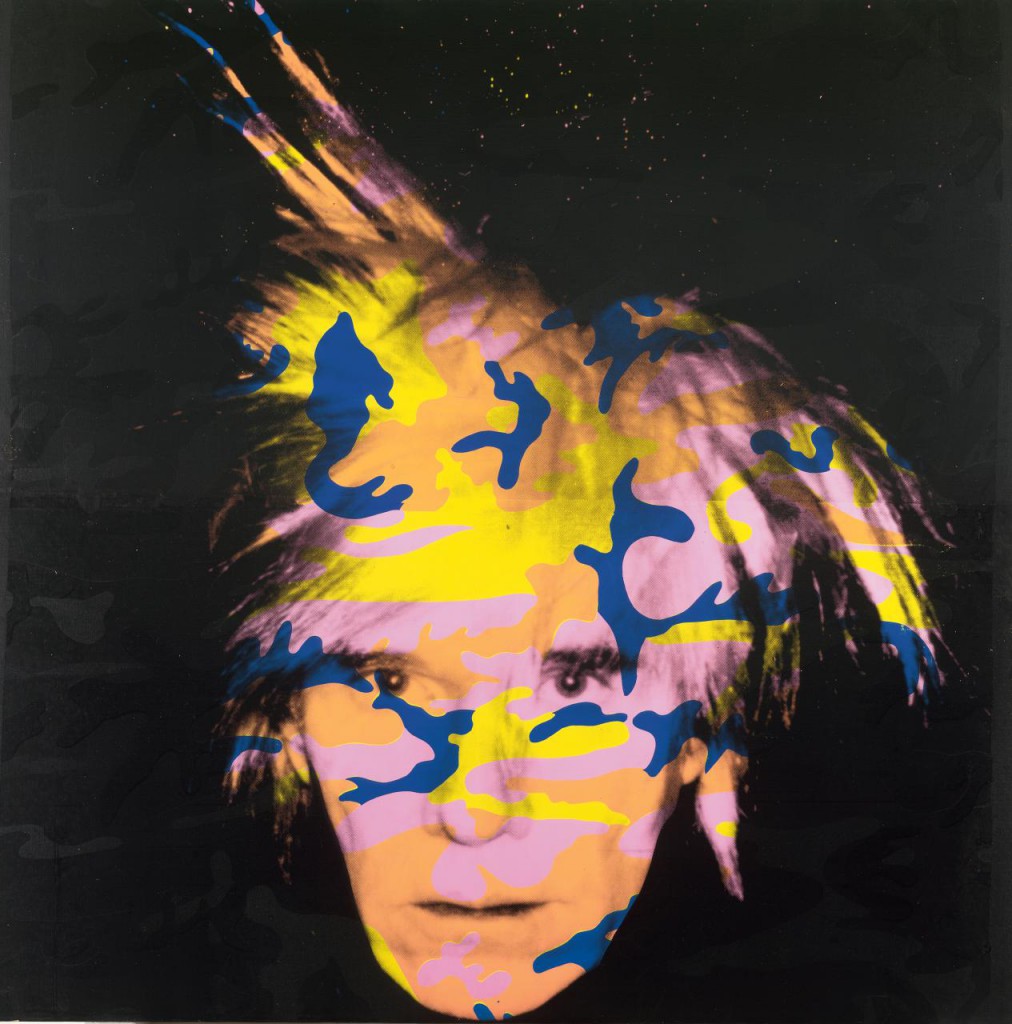

Andy Warhol, ‘Self-portrait no. 9’, synthetic polymer paint and screen-print on canvas, 203.5 x 203.7 cm, NGV, Melbourne.

Two years earlier, in 1986, Andy Warhol (born 1928 in Pittsburgh, died 1987 in New York City) produced his large Self-portrait no. 9, which depicts him peering at the viewer from behind a screen of fluorescent-coloured shapes. These organic forms float in front of him, seemingly screening the celebrity artist from his fans. The spiked hair on his disembodied head seems to be shooting into space. He refuses to give access to his inner self. Although Warhol was fascinated with fame and celebrity, he was able to distance himself from the public with an aura of mystery. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, ‘David with the head of Goliath’, 1609-1610, oil on canvas, Borghese Gallery, Rome.

The Italian Baroque artist, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), inserted gruesome self-images in many of his paintings. These ‘self-portraiture’ paintings of violence and death suggest an affinity with the perpetrator or the victim, or both. Between 1609 and 1610 Caravaggio painted David with the head of Goliath: the ghastly severed head of Goliath is painted in Caravaggio’s own image, with blood dripping realistically from the neck, the mouth gaping open. Whereas Durer and Raphael were deemed to be divinely Christ-like, Caravaggio is dehumanised as the anti-Christ by his contemporary biographers due to his police record of brawling and murder. In 1672, Caravaggio’s biographer, Giovanni Bellori proposed that physiognomy is destiny when he wrote that:

Caravaggio’s style corresponded to his physiognomy and appearance. He had dark eyes, black hair, and eyebrows, and this appears again, even naturally, in his painting . . . Later, driven by his peculiar temperament, he gave himself up to the dark style, and to the expression of his turbulent and contentious nature.

There is no sun in Caravaggio’s paintings, little daylight and less sky, which suggests that his use of chiaroscuro expressed his dark personality. Bellori wrote repeatedly about Caravaggio’s naturalezza (naturalism) and his determination to paint da vivo (from life). It is well known that the artist attended public hangings. The black void in the background accentuates death. Caravaggio has taken biblical iconography to another level by projecting his own fears of damnation not only in the image of the victim but possibly in the persecutor, David, as well. In fact, the David figure could be Caravaggio’s disguised image, the sad and compassionate expression reflecting hope for redemption. Caravaggio died soon after he painted this ‘self-portrait’.

Artemisia Gentileschi, ‘Judith Beheading Holofernes’, c. 1620, oil on canvas, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Another Italian Baroque artist, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1656), is known for her paintings that depict female avengers, often thought to be Artemisia’s disguised self-portraits. Given Gentileschi’s biography, which includes her accusations of rape by her father’s associate, Agostino Tassi, many scholars believe that the image of Judith in Judith Beheading Holofernes is the one most associated with Artemisia’s psychic and physical self, and that she used her features for the face of Judith. The painting depicts the biblical story of Judith in the act of cutting off the head of the Assyrian general, Holofernes, who was at the time laying siege to the city of Bethulia. The Jewish heroine, dressed in her finest garments, went to his tent with the intention of liberating her city from the enemy. When Holofernes was asleep Judith took a sword, and with the assistance of her slave Abra, cut off his head. Direct evidence is lacking and there is a danger in making subjective interpretations; however, it is easy to imagine that Artemisia Gentileschi may have projected her feelings of revenge, casting herself as Judith and Tassi as Holofernes, blood spurting out of his severed neck in dramatic fashion. Other theories include the suggestion that this painting is not about her life experience and revenge, but about the killing of her father’s art and defining herself as a female painter.

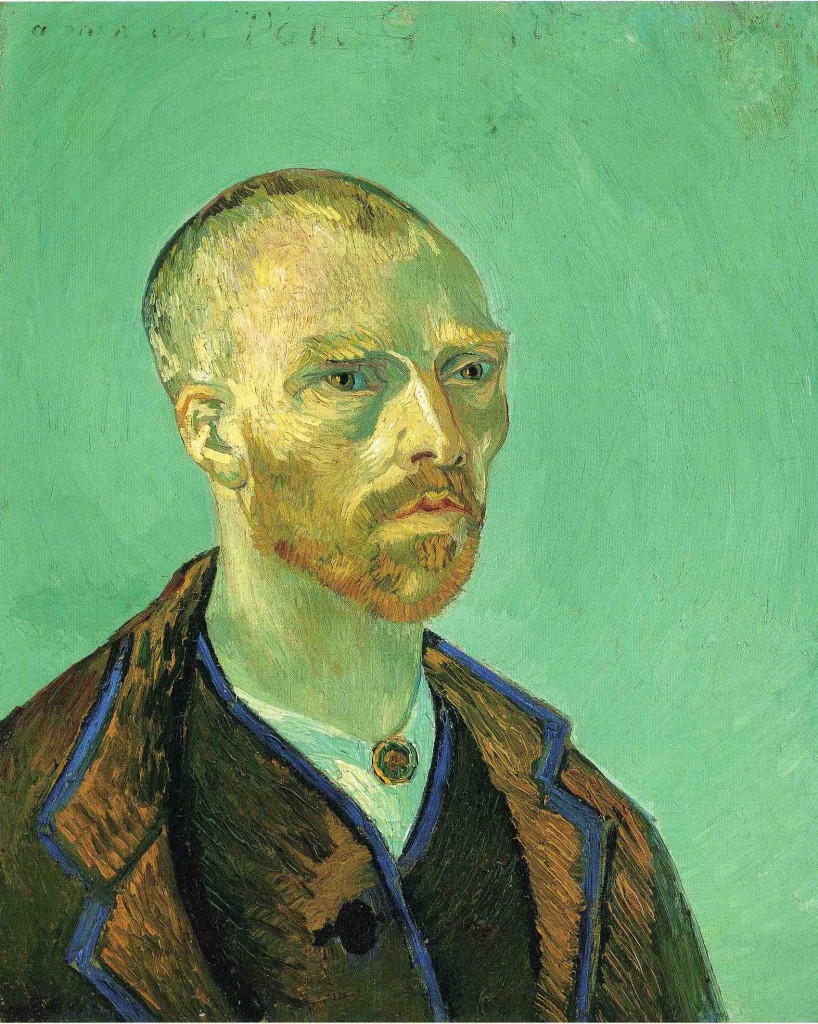

Vincent van Gogh, ‘Self-Portrait, dedicated to Paul Gauguin’, oil on canvas, 52 x 62 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge MA.

Finally, my fifth self-portrait selection eliminates shadows, bringing back colour and light. In September 1888, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), the Dutch Impressionist, shaved his head and painted himself with almond-shaped eyes. Van Gogh portrays himself as a bonze, a Japanese Buddhist monk. If you compare this self-portrait with others by van Gogh, it becomes clear that the artist exaggerated his facial features: his head is rounded, his cheeks are sunken, his eyes are slanted. Why this desire to transform his facial image? It’s well-known that Vincent was immeasurably influenced and fascinated by all things Japanese, especially Japanese woodblock prints as Japan opened its doors to foreign trade. When he moved to Arles in early 1888, the artist imagined that the surrounding landscape of southern France reflected the landscape of Japan, which he had never seen. He wrote to his sister, Wilhelmina, in a letter (9 and 16 September, 1888):

For my part, I don’t need Japanese prints here in Arles, because I am always saying to myself that I am in Japan. That as a result I only have to open my eyes and paint right in front of me what makes an impression. . . .

I also made a new portrait of myself, a study, in which I look like a Japanese.

But why the title: ‘Self-Portrait, Dedicated to Paul Gauguin’? Vincent van Gogh was obsessed with Gauguin, whom he enticed to Arles to paint with him. On 7 October 1888 Vincent wrote to his brother Theo after he received Gauguin’s self-portrait:

I have written to Gauguin in reply to his letter that if I might be allowed to stress my own personality in a portrait, I had done so in trying to convey in my portrait not only myself but an impressionist in general, had conceived it as the portrait of a bonze, a simple worshipper of the eternal Buddha. . . .

It is all ashen grey against pale Veronese (no yellow). The clothes are this brown coat with a blue border, but I have exaggerated the brown into purple, and the width of the blue borders. The head is modelled in light colours painted in a thick impasto against the light background with hardly any shadows. Only I have made the eyes slightly slanting like the Japanese

He sought to embody Japanese traditions of religion and community by “Japanising” himself, and by attempting to create an artists’ commune in Arles. Gauguin arrived a month after van Gogh painted himself as a Japanese Buddhist monk. They argued incessantly and Gauguin left soon after, leaving van Gogh disappointed and depressed. On 23 December 1888, Vincent van Gogh wrote:

I think Gauguin had become rather disheartened with the good town of Arles, with the little yellow house where we work, and especially with me.

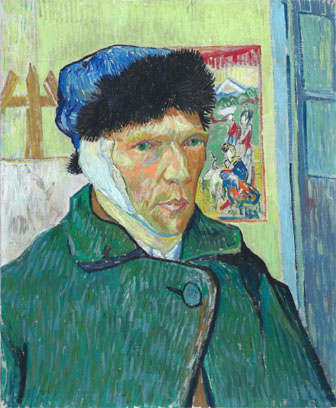

Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear’, 1889, oil on canvas, 60 x 49 cm, Courtauld Gallery, London.

In January 1889, Vincent van Gogh mutilated his ear and painted this melancholy self-portrait. He is standing in his studio with a Japanese print on the wall and a blank canvas on an easel behind him. This was his reality, and this self-portrait concludes my two-part study of self-portraiture.

***

The featured ‘masked’ self-portrait is by photorealist artist, Chuck Close, who fractures his facial features with inventive abstraction, filling the entire picture space.

Chuck Close, Self portrait, 2009, colour woodblock, QUT Art Collection, Brisbane.