In 1830, at the age of 60, the self-professed drawing maniac, Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), thought his best work was yet to come, and maybe it was, but the National Gallery of Victoria’s ‘Hokusai’ exhibition (closes 14 October) proves that his woodblock prints and paintings prior to the 1830s were indicative of a prodigious artistic talent. Displayed in the first room of the show, and created in 1798 at the age of 38, Hokusai’s woodblock print The craftsman’s workshop near Mt Fuji (image below), is a fine example of Hokusai’s sensitive observation of nature, and people as social animals, each with their own idiosyncrasies and foibles. According to the wall label, the print was produced for a poetry album and “indicates the New Year season and the coming of spring. A folding screen features prints of the rising sun with pine trees, plum blossom, bamboo and chrysanthemums. The traveller has collected some real plum blossom and attached it to his baggage.” Hokusai was perhaps the most significant artist of the Japanese Edo-period (1600–1868) art movement producing copious paintings for the popular ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world, woodblock prints that referenced the Edo (now Tokyo) ‘pleasure district’ with its beautiful women and Kabuki actors.

Katsushika Hokusai, ‘The craftsman’s workshop near Mt Fuji’, 1798, from ‘The mist of Sandara’ album, colour woodblock, 21.8 x 31.0 cm (image and sheet), The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto

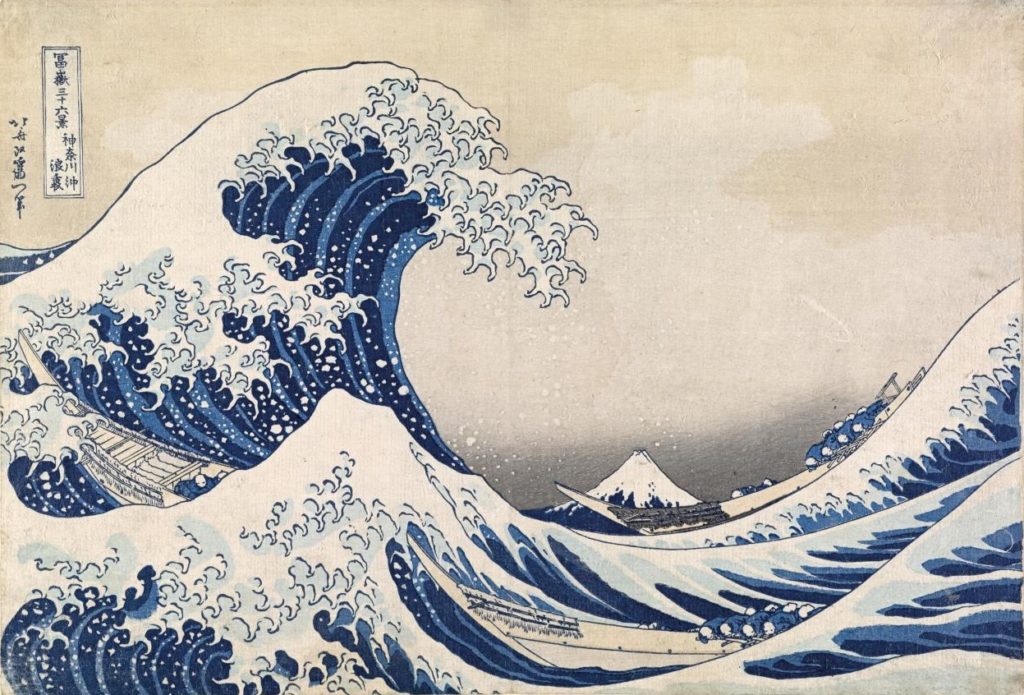

The magnet for most visitors to this NGV exhibition will be Hokusai’s The great wave off Kanagawa (image below). If we take a close look at the ‘Great Wave’ there is no doubt that Hokusai invented new ways of visualising his world, nature and human activity. Swift boats, as seen in this painting, transported fresh fish and dried sardines in the morning to fish markets off Edo Bay from villages on the Bohso Peninsula. We can sense human struggle as the boats battle the sea, with Mount Fuji, the sacred mountain associated with Shinto kami (spirits who live in nature, which I have written about here), as the focal, if distant, motif framed by the cresting wave. Traditionally, Japanese painting avoided deep-receding pictorial space; however, in the 1830s Hokusai cottoned onto elements of Western realism and vanishing-point perspective. The availability of Prussian Blue, mainly imported from Berlin, enabled Hokusai to widen the tonal range.

Katsushika Hokusai, ‘The great wave off Kanagawa’, 1830–34, from the ‘Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji’ series, colour woodblock, 25.7 x 37.7 cm (image and sheet), purchased 1909, one of the original 200 prints, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

To speak of the ‘Great Wave’ is to speak of one of the most well-known and revered images in art history, a religious icon of sorts. So it is no surprise that this picture is the ‘face’ of the NGV ‘Hokusai’ exhibition: featured in newspaper ads; on the covers of the NGV July/August magazine program insert, the ‘What’s On’ booklet, and the exhibition catalogue; printed on scarves, t-shirts, posters, mugs, bags, sketch books, mirrors, and even on skateboard decks—all for sale in the exhibition shop (now elegantly called the NGV design store). The Gallery is certainly ‘hyped-up’ for Hokusai, hoping that the public will respond.

As the NGV website tells us, this exhibition “features 176 works from the Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto, and the NGV Collection that encompass the artist’s remarkable seventy-year career.” A whopping three sets of book illustrations and the complete set of fifteen volumes of Hokusai’s Manga are also on display. This exhibition is big, very big; but, as one of my art history students, who recently visited the exhibition, opined: “perhaps too big?” The British Museum in London has just closed its Hokusai exhibition, Beyond the Great Wave, and at any one time there were only 110 works on display due to concerns about the prints’ sensitivity to light. Works were rotated regularly, which created a more focused, and less overwhelming, viewing experience.

NGV Japanese art curator, Wayne Crothers, is an insightful scholar of Japanese art, and he has designed this exhibition to allow free-flowing movement (apart from the bottle-neck in the entrance) through ‘rooms’ across two large ground floor galleries based on themes such as Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji, 1830–34; A Tour to the Waterfalls in Various Provinces, c. 1832; Remarkable Views of Bridges in Various Provinces, c. 1834; Eight Views of the Ryūkyū Islands; and One Hundred Ghost Stories, c. 1831; and subjects of birds, flowers and historical poetry.

It is a relief that the NGV hasn’t reproduced the same exhibition design as the recently-closed Vincent van Gogh blockbuster, with its cramped viewing spaces making it impossible for relaxed viewing. Taking guided tours in this busy exhibition must have been a challenge. I was intrigued that a large room was allocated to, believe it or not, Japanese woodblock prints, which, although a major influence on van Gogh’s stylistic technique, would have left many visitors scratching their heads and thinking: “Have we stumbled on a preview of the Hokusai show?”

And so to a few of my favourites from this comprehensive NGV ‘Hokusai’ exhibition …

Hokusai’s exquisite close-up pictures of birds and flowers are often overshadowed by his paintings of people and landscapes, but his acute observations of birds in flight and their seasonal habits are masterfully translated onto paper, often reflecting human emotions. The writing reveals the names of the birds and flowers and a contemplative poem. Poetry in motion?

Katsushika Hokusai, ‘Peonies and canary’, c. 1834, printed late 19th century from an untitled series known as ‘Small flowers’, colour woodblock, 25.7 x 18.5 cm (image and sheet), The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto

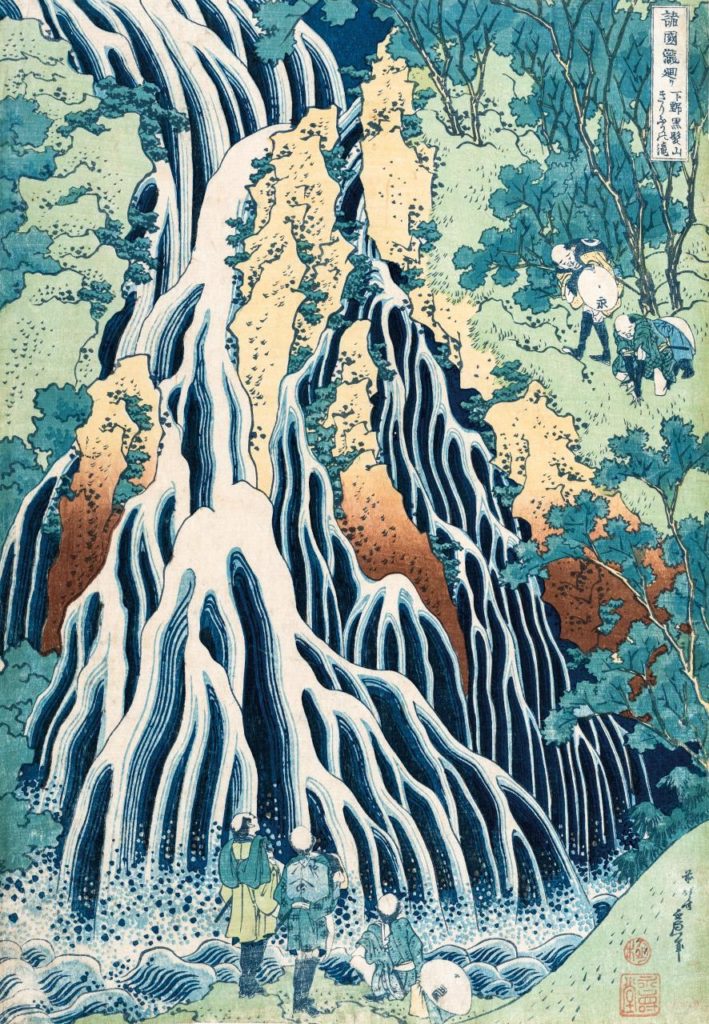

In his series, ‘A Tour to the Waterfalls in Various Provinces’, Hokusai painted eight waterfalls north of Edo. Just like mountains and streams, waterfalls are not only signifiers of nature’s beauty for the Japanese, but also of the presence of Shinto kami. Buddhists undertook pilgrimages to these wilderness places. Hokusai’s interpretation of Kirifuri Waterfall (image below) with its cascading water and foaming spray at the base is inventive, achieving maximum impact in the vertical format. Three pilgrims look up in awe at the sublimity of the sight while two more viewers scurry up the side of the waterfall.

Katsushika Hokusai, ‘Falling mist waterfall at Mt Kurokami in Shimotsuke Province’, c. 1832, from ‘A Tour to the Waterfalls in Various Provinces’ series, colour woodblock, 36.5 x 25.6 cm (image and sheet), The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto

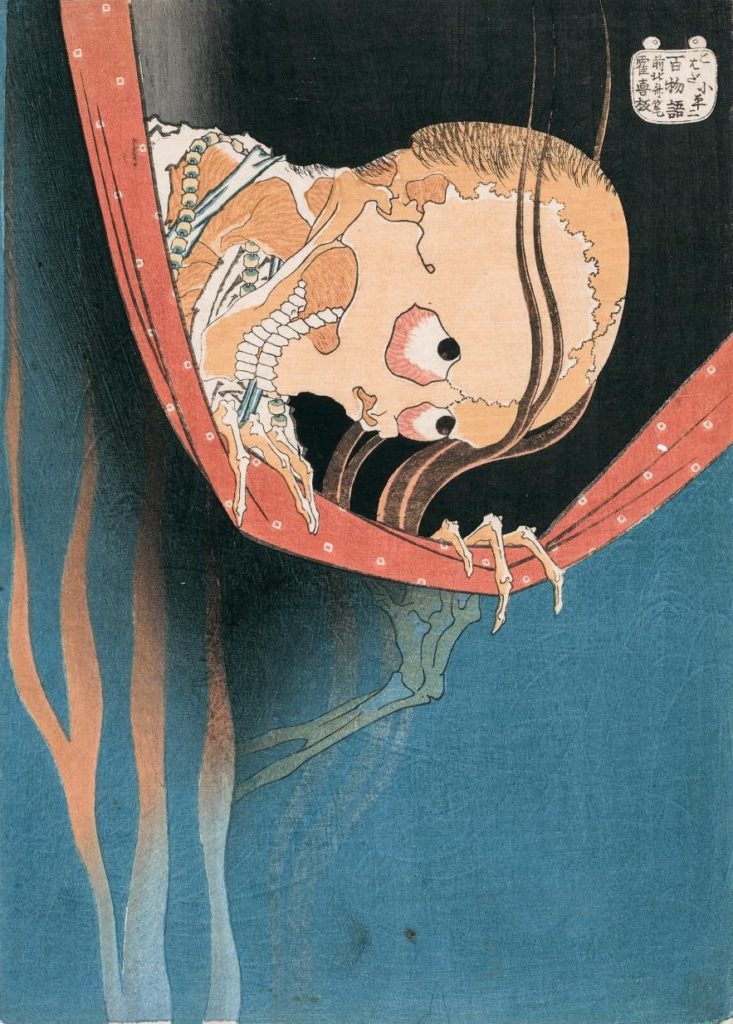

As his career developed, Hokusai gave full rein to his, sometimes bizarre, imagination. This is particularly noticeable in his ghoulish woodblock prints from the ‘One Hundred Ghost Stories’ series based on the popularity of storytelling traditions that feature tales of betrayal and reprisal. A smallish central room with black-painted walls displays five ghost story images including The ghost of Kohada Koheiji (image below). The story goes along the lines that Kohada Koheiji, a second-rate kabuki actor who frequently played the role of a ghost, was murdered by his wife and her lover. Koheiji comes back from the dead to haunt them. In this painting, Hokusai depicts the ghostly skeleton of Koheiji pulling back the mosquito net over their bed with his bony fingers and looking at them mischievously.

Katsushika Hokusai, ‘The ghost of Kohada Koheiji’, c. 1831,from the ‘One Hundred Ghost Stories’ series, colour woodblock, 26.3 x 18.7 cm (image and sheet), The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto

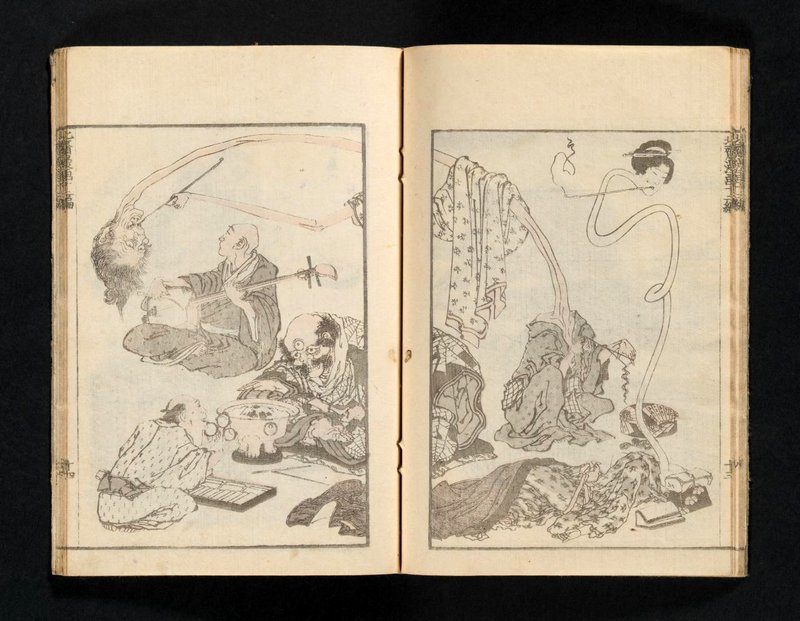

To add variety, monitors have been inserted into a wall to illuminate images of Hokusai’s Manga, sketches of comical caricatures that influenced the modern form of comics known by the same name. Twelve volumes of Hokusai’s Manga published before 1820, and three more published posthumously include thousands of drawings of animals, religious figures, and people going about their ‘everyday’ life. From volume 12 (image below), a scene from a ghost story depicts a musician entertaining two long-necked woman, and a three-eyed ogre is receiving a three-lens set of spectacles from an optometrist.

Hokusai Manga Vol XII, 1834; colour woodblocks, 57 pages, paper cover, stitched binding, 22.7 x 29.0 cm (image and sheet), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

In 1839, a fire destroyed Hokusai’s studio and much of his work. By this time, his career was beginning to fade as younger artists such as Andō Hiroshige (1797-1858) became increasingly popular. But Hokusai never stopped painting. In 1834, at the age of 64, he wrote: ‘From the age of six I had a mania for drawing the forms of things. By the time I was fifty I had published an infinity of designs; but all I produced before the age of seventy is not worth taking into account. At seventy-three I learned a little about the real structure of nature, of animals, plants, trees, birds, fish and insects. In consequence, when I am eighty I shall have made still more progress; at ninety [I] will understand the essential nature of things, and at one hundred this understanding will be divine. At one hundred and ten each dot and stroke I paint will be animated. Those of you who have sufficient longevity, can give evidence to the truth of my words’. He didn’t live 110 years, but what he had achieved when he died at the age of 89 was truly astonishing.

Post script: Dr Gary Hickey, who introduced me to Japanese art at The University of Melbourne, has curated an exhibition of Japanese art, Melodrama in Meiji Japan, showing until 27 August at the National Library of Australia, Canberra.

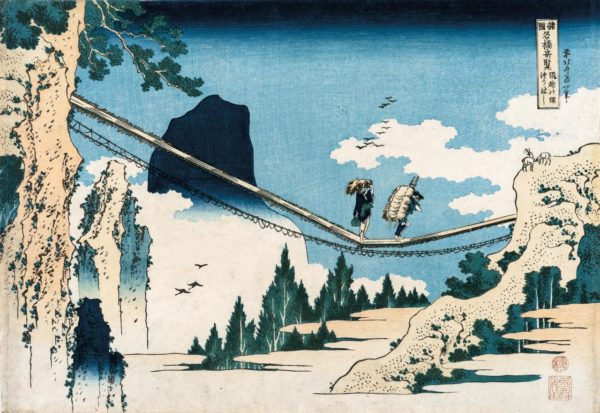

Featured image: Katsushika Hokusai, The suspension bridge on the border of Hida and Etchū provinces, c. 1834, from the Remarkable Views of Bridges in Various Provinces series, colour woodblock, 25.5 x 37.2 cm (image) 26.8 x 38.5 cm (sheet), The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto