As the working year like no other winds down, there is no better time to find some personal space to reflect and re-energise. I suggested to an author, whom I’ve been mentoring for more than a year, to book a free timed-entry ticket to our local art gallery to help her unwind, refresh, or maybe even invigorate her ideas. The National Gallery of Victoria International (NGVI) re-opened two days ago, launching its Triennial 2020. Although her academic year is finished, this talented author has expressed how the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted her perspective, and that she was experiencing a brick wall as she pushes towards the deadline to submit her commissioned manuscript by mid-2021.

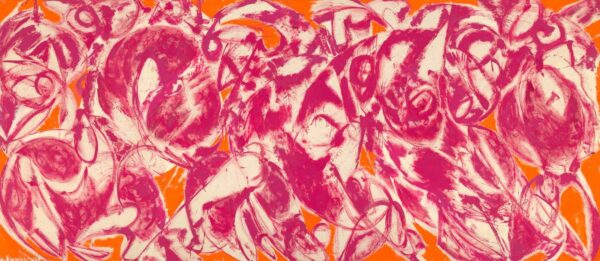

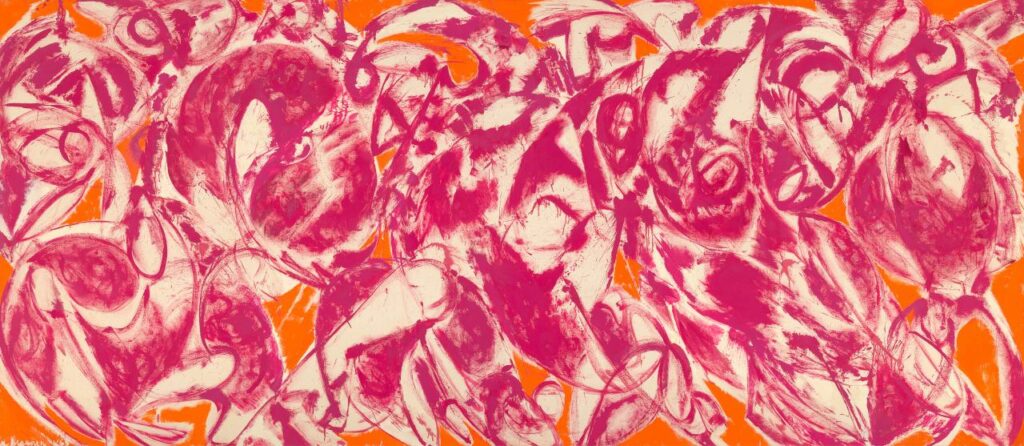

I recommended seeking out two NGVI mid-twentieth-century abstract paintings: Lee Krasner’s Combat (1965) and Mark Rothko’s 1956 Untitled (Red). Unfortunately, she reported that Combat was not on display, but viewing Krasner’s painting is certainly worth a return visit to NGVI when it’s back ‘home’. The vibrant pink and orange swirling cavalcade galloping across its 410.4 cm width of canvas is suggestive of a harmonic and rhythmic world of positive creative energy. It is a totally immersive viewer experience.

According to French philosopher and literary critic, Michael Foucault (1926 –1984), a creation of literature (‘What is an Author’ 1984), or we could say, a work of art, does not belong to the alleged maker because it impedes the circulation of ideas. Some take his theory further and suggest that the work belongs — or ought to belong — to the perceivers. In other words, as art critic James Elkins argued (‘Critical Theory’ 1996), viewers speak for the works and make sense of the artistic creation before them according to their experiences — their historical, social and psychological state. For me, the high-key colour and dynamic calligraphic movement of Lee Krasner’s Combat energises my senses with its ‘explosion’ of line and movement. My advice to viewers of art is: don’t take ‘for gospel’ what an ‘expert’ may tell you about a work of art. It is more important for you to perceive the work as you see it. The same goes for a work of literature.

As controversial American artist Jeff Koons said: “Art demands nothing. You never have to bring to art anything other than yourself. The only thing that art really is, is the essence of your own potential.” And so, for many, a work of art can be a conduit of ideas, or a release of ideas. Koons’ NGV Triennial exhibit, Venus (2016 -2020), certainly implicates the viewer within the work. As the wall label tells us: “The use of reflective surfaces was to connect the work to philosophy and the experience of belonging. … Reflections tell the viewer that nothing is ever happening without them.”

It is not unusual for writers, whether they are writing fiction or non-fiction, to get stuck trying to formulate ideas. Once ‘unstuck’, the next challenge is determining the right literary techniques and language to present those ideas/theories in the form of a readable fictional story or non-fiction ‘narrative’.

Abstract paintings such as Combat erase any semblance of narrative in preference for a more spiritual, enlightening or aesthetic experience. In the 1940s, influential American art critic Clement Greenberg (1909 –1994) promoted the elimination of subject matter in all art forms as a means of focusing on creative expression, or the creative act. He argued that narrative was the domain of literature.

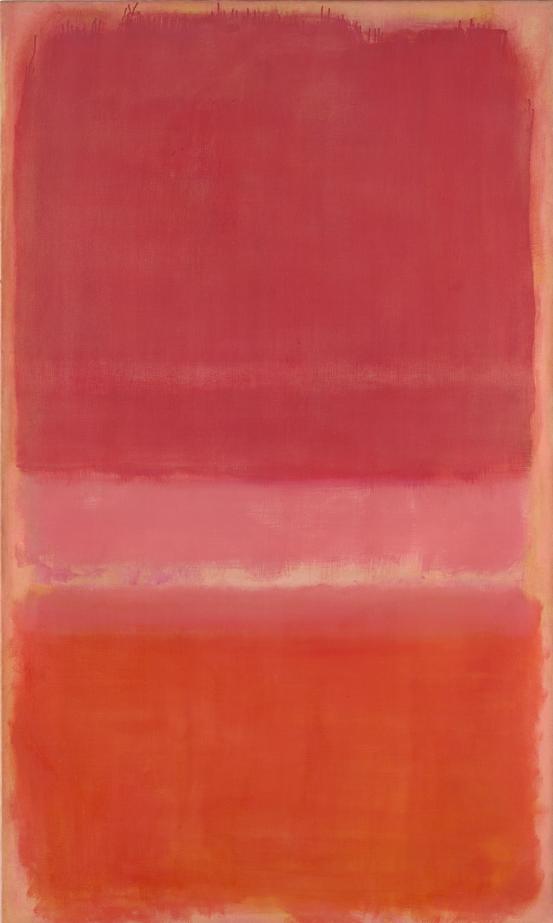

Amid the exhausting turnover of temporary exhibitions at the NGV, I can usually rely on Mark Rothko’s Untitled (Red) to be hanging on a white wall on NGVI’s level two. Like Lee Krasner (1908 –1984), Mark Rothko (1903 –1970) belongs to the generation of American abstract expressionists who emerged in New York during the 1940s. The essence of abstract expressionism was the spontaneous expression of the artist’s state of mind while working on each artwork. In turn, the viewer is encouraged to search for his or her individual emotional engagement with, and response to, the work — to release objectivity and meditate — and ignore the clatter of external noise and words.

Mark Rothko, ‘Untitled (Red)’, 1956, glue, oil, synthetic polymer paint and resin on canvas, 209.5 × 125.3 cm, NGV, Melbourne.

Rothko’s abstract arrangement of overlapping and merging variations of the colour red in Untitled (Red) serves as an aid to meditation, silencing the mind rather than inflicting interpretations on the spectator. Boundaries dissolve at the blurred, at times oscillating, edges of fields of colour, making this work totally immersive for the focussed viewer, who can re-energise by arriving at a personal state of stillness beyond the colour fields.

The task of deep contemplation of a work of art requires us to draw upon our personal experience and imagination. If achievable, the process strengthens our thinking strategies and helps us focus on creative pursuits such as formulating ideas for a writing project and then finding the right words to express those ideas.

I have been one of the lucky ones in 2020 because writers have been busily working on their projects during the pandemic, and requests for mentoring, manuscript appraisals and/or editing have been constant. I even did a bit of teaching. Consequently, I have been busier than ever, for which I am grateful.

However, even though there have been constant opportunities to view art digitally in 2020 thanks to the ingenuity of art curators across the globe, I have missed the stimulation of visiting galleries and museums. Standing quietly before a favourite NGV work of art ‘in the flesh’, preferably without the usual gallery noise, and allowing my senses to respond, re-energises my thought patterns. I did so today. It was the perfect way to reboot after an exhausting year.

If you are ready to have your writing edited, or you would like an assessment of your writing project, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then please email me via my contact page with a brief overview.

If you are ready to have your writing edited, or you would like an assessment of your writing project, whether it is a complete manuscript or a work-in-progress, then please email me via my contact page with a brief overview.

My editing is based on the Australian Style Manual (ASM) unless an author has been commissioned to write a book using the publishing house style guide. In particular, editing academic writing requires the editor to adhere to the preferred style and referencing of the university department or publisher.