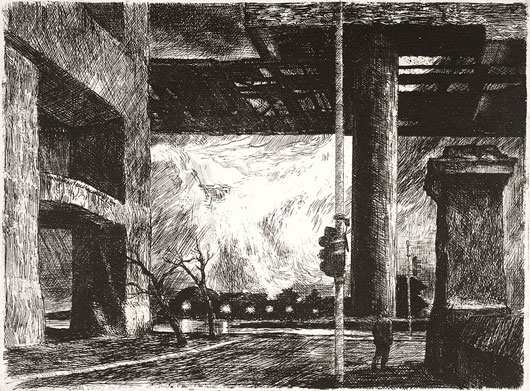

Cavernous interiors with staircases spiralling through claustrophobic space, and derelict buildings, are often described as communicating a Piranesian mood. You can be forgiven for not having heard of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778). He was an Italian etcher, architect and printmaker, who achieved fame for his revolutionary etchings of real and imaginary buildings that featured ancient Roman ruins and fantastical underground dungeons. Piranesi’s surreal prisons (Carceri) are known to have inspired the designers of the computer game ‘Dungeons & Dragons’. Now’s your chance to be hypnotised by Piranesi’s architectural dreamworld: Melbourne is hosting three Piranesi exhibitions across town.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Remains of the Aqueduct of Nero’, ca. 1760-78, etching, Baillieu Library Collection, The University of Melbourne.

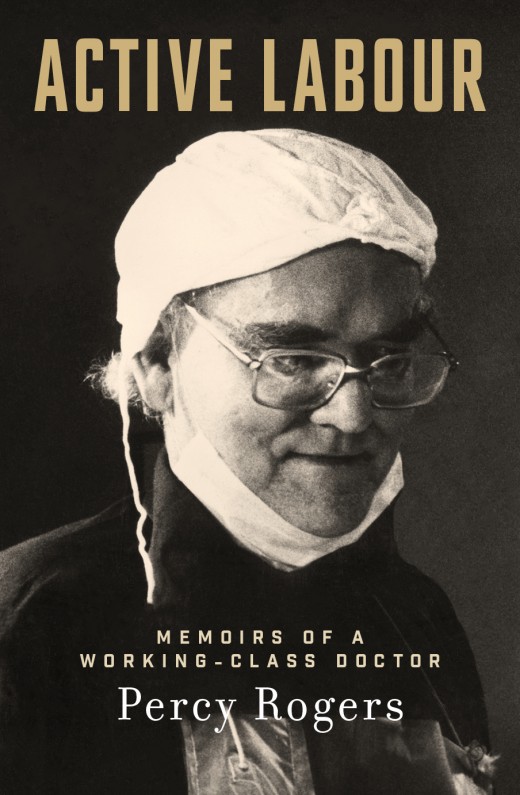

During the eighteenth century, Rome was crumbling, its buildings overgrown with weeds and creepers; Piranesi’s etchings both glorified ancient Rome and highlighted the city’s demise. Grand Tourists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries identified emotionally with Rome and they bought innumerable Piranesi prints that would give weight to their amateur sketchings of the ‘romantic’ ruins of Rome. Piranesi’s series of views or vedute from his the Vedute di Roma, such as views of the Pantheon and the Colosseum, were high on their lists of must-have collectibles.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Veduta dell’ Anfiteatro Flavio, detto il Colosseo (View of the Colosseum, or Flavian Amphitheatre)’, 1765–78 impression, etching and engraving, State Library of Victoria.

Born close to Venice in 1720, Piranesi went to Rome at the age of 20 as a draftsman for the Venetian ambassador, with the intention of becoming an architect. He studied with leading printmakers of the day including Giuseppe Vasi, the foremost producer of etched views of Rome. Settling permanently in Rome in 1745, Piranesi quickly developed his highly original etching technique, producing rich textures and bold contrasts of light and shadow. By 1747, Piranesi had begun his series, the Vedute di Roma, and he created about 2,000 plates until his death in 1778.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Piazza del Popolo’, ca 1750, etching, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

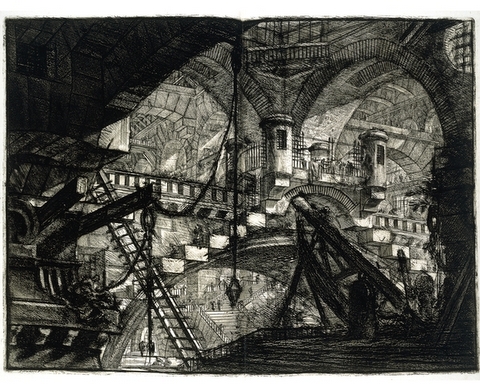

These days Piranesi is probably best known for his Prisons (or Carceri) etchings of labyrinthine prison interiors, which were constructions of his imagination and pushed the limits of perspective and spatial illusion. This form of veduta, the capriccio, combines life-like architectural elements in a rather strange fashion. The English word ‘capricious’ derives from capriccio and suggests the irrational. Piranesi’s ‘prison’ etchings convert ancient Roman ruins into elaborate, visionary dungeons filled with stairways that go nowhere, and with mysterious scaffolding and instruments of torture. As can be seen in the following etching, drama is achieved through contrasts between the lit spaces and the deep shadows. Diminutive figures appear doomed to climb endless staircases without hope of release. As such, Piranesi’s imaginary prisons held a mesmerising fascination for later Romantic writers, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Edgar Allen Poe (‘The Pit and the Pendulum’ 1842).

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Prisoners on a Projecting Platform’, from ‘Carceri’, 1749-50. Edition: Francesco Piranesi, 1800-07, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

Piranesi in Melbourne

Both The University of Melbourne (Baillieu Library) and the State Library of Victoria (SLV) have distinguished collections of Piranesi prints. Many of the bound volumes at the SLV were from the collection of George IV, while those from the Baillieu Library were acquired from James Alipius Goold, Melbourne’s first Roman Catholic archbishop.

The Australian Institute of Art History, in collaboration with the Baillieu Library and the SLV, hosted a conference on Piranesi and the Impact of the Late Baroque on 27 and 28 February 2014 at The University of Melbourne. The conference brought together local and international speakers including Jane Clark (Senior Research Curator at MONA, Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art, in Hobart). Clark presented a paper on ‘Piranesi and MONA: inspiration or retrospective myth’, drawing our attention to an article in the prestige car magazine, Trend Visions. MONA was described as “a maze of Piranesi-like architectures”. Since its opening in 2011, many visitors to MONA have compared the subterranean art galleries with Piranesi’s Carceri. However, according to Clark, MONA’s owner David Walsh, says “there is no such connection . . . Piranesi wasn’t in anyone’s mind” when he and Nonda Katsalidis conceived their design. Just a coincidence? Or just an unconscious influence?

Currently, there are three exhibitions in Melbourne that focus on Piranesi’s vision. Rome: Piranesi’s vision runs until 22 June at the SLV. Curated by Dr Colin Holden, this is the largest exhibition of Piranesi’s work ever seen in Australia. Most of the prints focus on his Vedute di Roma that capture the essence of Rome and the era of the Grand Tour. The layout and design of the exhibition enhances the visual enjoyment—the walls are painted gold and feature decorative panels. Piranesi’s prints are interspersed with engravings and etchings by his contemporaries including Vasi, and there are paintings by Giovanni Paolo Panini. Glass cabinets display an assortment of Piranesi publications on classical Roman buildings with architectural cross-sections that show off Piranesi’s prolific and exquisitely detailed work. Trot along and decide for yourself whether Piranesi is the most important engraver and printmaker of the eighteenth century, and the greatest architectural artist of all time.

Colin Holden’s excellent book, Piranesi’s Grandest Tour: From Europe to Australia, is being sold in conjunction with the exhibition. Holden makes interesting comparisons between Piranesi’s ruins and the work of Australian artists such Russell Drysdale’s crumbling and deserted outback pub in Hill End (1952).

Rome: Piranesi’s vision

Keith Murdoch Gallery, State Library of Victoria

328 Swanston St. Melbourne

FREE

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Veduta interna del Panteon (View of the interior of the Pantheon)’, 1760s-70s, etching and engraving, State Library of Victoria.

The small exhibition in an upstairs space at The University of Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum of Art, The Piranesi Effect, runs until 25 May and complements the SLV exhibition by using contemporary art as a guide to understanding Piranesi; in particular, his Carerci prints. The seven New Zealand and Australian artists include Rick Amor, Michael Graf, Mira Gojak, Andrew Hazewinkel, Peter Robinson, Jan Senbergs (his recent work is featured here) and Simon Terrill. I was mystified to read on the wall label that: “None of the works by these artists were made with Piranesi in mind. They were made with other intentions, and all have rich histories and associations which until now did not include Piranesi . . .” Instead, apparently, these works “remind” us of elements fundamental to the effects created in Piranesi’s works: his dramatic use of scale, viewpoint, lighting and perspective. This requires a stretch of the imagination because most of the contemporary works that face Piranesi’s exquisite renderings of architecture and imaginary places, with their psychological chiaroscuro, are a little too cryptic. For example, although the blocks of chains that Peter Robinson has built from lightweight polystyrene (Vinculum, 2008) suggest oppression and confinement, the work lacks the presence and solidity—and the dark imagination—that is embodied in Piranesi’s Carceri engravings and etchings.

Peter Robinson, ‘Vinculum’ (detail), 2008, polystyrene. © Peter Robinson. Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne.

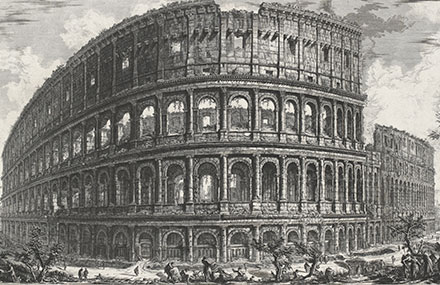

However, there are works in the exhibition that surely were created with Piranesi in mind. Colin Holden in his book on Piranesi points out that one of the artists, Rick Amor (born 1948, Melbourne), has been attracted to Piranesi’s “oddness” and “strange emptiness” since he first began to explore art. Rick Amor’s dark and brooding Outlying districts (below) recalls the monumental scale of Piranesi’s structures that dwarf the human figure.

Rick Amor, ‘Outlying districts’, 2001, etching, 23 x 30.5 (plate). © Rick Amor. Courtesy of the artist and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne.

In collaboration with the Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Melbourne, there is a third Piranesi-related exhibition running until 30 April. This photographic exhibition, A Traveller’s dream: Piranesi and Rome features photos by Graziano Panfili, a multi-award winning Italian photographer, based near Rome, who specialises in social documentary, street and art photography. Panfili’s photos are dream-like images of Roman views and buildings immortalised by Piranesi.

Piranesi’s unparalleled accuracy in depicting a view, his personal expression of a building’s romantic grandeur, and his technical mastery, made his engravings some of the most original and impressive representations of architecture to be found in Western art. The dramatic art of Piranesi is consistent with that of the late Baroque artist, but what makes him so unforgettable is the way he draws us into his psychological fascination of the sublime, and the mysteries and impermanence of life.

I need to produce great ideas, and I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it. Giovanni Battista Piranesi

If you want more on Piranesi then read this by Wendy Thompson from the Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.